#009 - Product Management Lessons by Meituan Co-Founder - Pt 8: Timing

8 mins read - Window of Opportunity, Timing, Why big & small companies fail to capture opportunities

Let’s get you up to speed:

Wang Huiwen is the co-founder of Meituan, who recently retired at age 42 with an estimated net worth of >US$2B. He opened a Product Management course at Tsinghua University in September 2020. This article and others in this PM series are my translation and edits based on a compilation of the content of his course shared online. You can see other articles in this series here.

The Window of Opportunity lasts for 3 Months

Ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius said that timing isn't as good as geographical advantages, and geographical advantages aren't as good as favorable human conditions. (Note: A loose translation of 天时大于地利,地利大于人和. A simpler version - right time, right place, right people). That may apply to war, but I think in business, it's actually the opposite - timing > environment > people. The importance of timing cannot be over-emphasized. Entering too early or too late both lead to failure. The window of opportunity for a category usually lasts for three months.

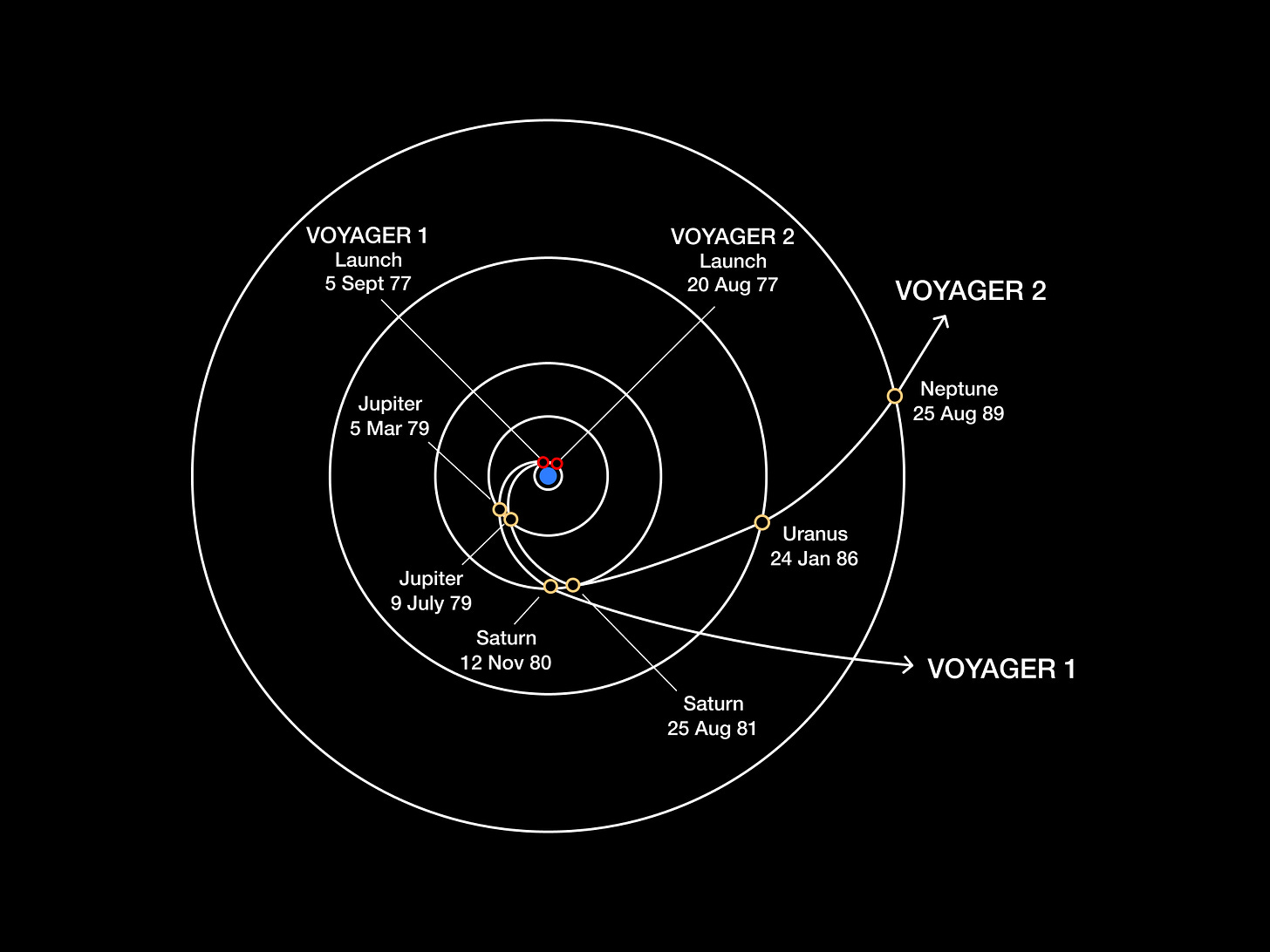

(Related Reading: A brilliant article by Tiago Forte on Windows of Opportunity, you’ll get the above image)

The latest, hottest Internet trend in China is community group buying - basically, a group of people orders together, the goods get delivered the next day and people pick up the goods at a central location then split among themselves. In the last quarter (2020Q2), companies with a significant scale - Meituan, Pingduoduo, Alibaba, Didi, JD, all rushed into community group buying. It's now or never.

Another example is group buying. Meituan went live on 4 March 2010. In the quarter that followed, hundreds of new entrants emerged. The companies that didn't enter in those three months were doomed from the start.

For most industries, the time window is very narrow, like a lightning in the sky. The thunder strikes and lightning flashes, the air opens up, and the light shines, then the opportunity disappears into the darkness.

Judging Timing

The questions that we need to answer are how do we judge the timing, and how can we be sure that our entry is the right move and not stepping into a bubble.

(Note: Wang Huiwen gave examples in 1. Artificial Intelligence, which was popular in the late 1980s; 2. Community group buying, which already had a wave in 2018; 3. 3G startup waves pre-2009; 4. Mobile Internet - Ganji, as part of its competitive strategy against 58.com, invested heavily in mobile with Nokia’s Symbian OS in 2008 but failed due to immature technology. Edited for brevity.)

The point is, timing is very hard to grasp. For every opportunity, there'd be a lot of founders rushing in, and there'd be a lot of investors pouring money into it due to FOMO (the fear-of-missing-out). As such, even for the wrong opportunity, you may still get funded.

The general rule in life and business is that the more important something is, the more difficult it is to make a good judgment about it. For a big company, it's not any easier to judge timing than it is for a small company. There are two rules that I apply.

“If you believe something will eventually happen, try every 3 years." - Marc Andreessen (Note: I can't find where or if he said it)

As long as you can stay alive, it's always better to enter early than to enter late. - Me (Wang Huiwen)

How to stay alive is difficult for both big and small companies.

The Difficulty for Big Companies

The difficulty for big companies is that everyone wants to get promoted. The committee in charge of promotions usually is controlled by managers from established business lines. People who work in new business lines usually do not have much say. Business lines with fast growth confer speedy promotions, and it’s much tougher to get promoted in slow-growing business lines.

In addition, the committee members don’t understand the new businesses that well. So as long as there are visible results, they’ll let you pass. On the other hand, if you don’t have visible results, you don’t get promoted. There are also lateral movements internally within the company.

All these result in company employees chasing momentum - if a business is doing well, everyone wants to go there; if not, everyone wants to leave. Consequently, if a business doesn’t have much progress for a long period of time, the people who remained there may not be the best talent - even if an opportunity comes, they won’t be able to make it work.

Therefore, chasing a new opportunity is a tremendous challenge in big companies. The person-in-charge must have a strong will as well as leadership support.

The Difficulty for Small Companies

The difficulty for small companies is that if there is no progress after a period of time, the best talents within the team will be poached.

When the first person leaves, you may think that he is a traitor of the cause. A few more people later, you’d feel that the cause has betrayed you. You start to have doubts. Maybe you’ve gone the wrong direction or picked the wrong industry or the wrong approach. Or maybe you don’t have enough talent, or enough resources, or your investors are not good enough. You get into a whole sequence of self-denial.

Additionally, a startup usually has a frontman and that’s usually the CEO. The CEO needs to meet with investors, flirt with journalists, and recruit people. Gradually, the CEO spends less time on the core business. The CTO is the one that’s actually running everything.

The CEO sets the direction in the beginning. After a period of time with no progress, the CTO who does the real work will be tempted by many outside offers, and also start to have second thoughts about the business.

If the CEO says, “There’s nothing wrong with the direction. Let’s push on.”, the CTO may feel it’s hard to communicate with the CEO - s/he doesn’t listen to the team’s opinions and feedback or his/her work as the CTO is not recognized and respected, and leave.

If the CEO listens to the CTO and revises the product, the revision may overturn the CEO’s previous idea. If the revisions don’t work out, after two attempts, the team members will face more pressure from their families (i.e. “get a real job“). And if further attempts yield no progress, then the team will disband. As such, most startup teams disband at the end of the second year.

No matter big or small companies, the startup team is as fragile as the human body - without a few minutes of breathing, it dies. The closer the entry point is to the appropriate time window, the shorter you stop breathing - you want that to be as short as possible.

How Does A Window Of Opportunity Open

The other insight is that all the great needs most definitely have been tried many times in the wrong way or at the wrong time. If you’re fortunate enough to be the first to do something, there is a high probability that you’ll get it wrong. If you’re not the first, then people would say, “You know, many people have tried and failed.”.

The question that we need to answer is how does a window of opportunity open. It’s usually formed by a combination of many underlying factors - societal, economic, technological, etc. The PEST (Political, Economic, Social, Technological) framework comes into play - it’s usually the changes in these factors that result in a short window of opportunity.

Change In Technology

The most frequent change is by technological advances that create new possibilities for cost or experience improvements.

One of the main reasons that lead to the rise of the food delivery industry is the proliferation of smartphones. Since the advent of the iPhone, the costs of smartphones have been steadily decreasing (there are even $100 smartphones now), which allows every delivery driver to be equipped with a smartphone. If every delivery driver had to be equipped with an iPhone, the costs of delivery would be much higher. Similarly, if the costs of e-bikes were too high, delivery drivers couldn’t afford them either.

If the merchant’s order management software were operating on a desktop, the costs would also be much higher. However, if it’s on a smartphone, it’d be much cheaper and more convenient.

Change in Industry Practitioners’ Cognizance

In many industries, if you at it after the fact, at a certain point, the technology, infrastructure, and costs may already be supportive, but industry opportunities have not yet formed.

That’s because, at the beginning of an industry, practitioners have many misunderstandings. These misunderstandings require repeated attempts by practitioners to eliminate them before finding the correct method. It’s like Thomas Edison inventing the light bulb. He had to try thousands of possibilities before finding the right material. (Note: carbonized bamboo filament) Many teams working at the same thing will accumulate to the overall industrial cognizance of what works and what doesn’t.

For example, in building Xiaonei, we applied the lessons that we learned from building our first social network in 2003. We made fewer mistakes than others and did more things right. One insight was that social networks based on real identities have a higher user stickiness. (Note: Explained in #003 Network Effects) We didn’t have that understanding ex-ante; we only gained that after our first social startup. The other insight was that the idea that social networks need to have excellent user experience to achieve exponential user growth is wrong, which is a very counter-intuitive one. As such, when we were building Xiaonei, we weren’t single-mindedly building product features but spent more time on marketing and promotion.

These two insights helped Xiaonei to win. In the first social networks wave, some people had the first insight but not the second, some had the second but not the first. No one synthesized enough correct insights together.

In the early years of Social, there was a popular theory called Six Degrees of Separation, and everyone built their networks around six degrees of connections. (See: Six Degrees patent) However, at that time, the server load couldn’t possibly handle that much data. When building Xiaonei, I said that I think we can at most do 1.5 degrees. Wang Xin (Xiaonei and Meituan CEO) said, 1.5 degrees will do.

In conclusion, the correct cognizance didn’t just exist in someone’s brain since the beginning. But in the progress, different people grasped different pieces of correct understanding. And finally, someone aggregated all the pieces of understanding to form a comprehensive product. This cognizance is the collective intellectual property of the startup community.

Time In The Market, Not Timing The Market

Facebook might seem to get everything right from the get-go, but that’s not the case. In the early days of Facebook, they had a president named Sean Parker. He was instrumental to the early Facebook. (Note: "If Mark ever had any second thoughts, Sean was the one who cut that off." - Peter Thiel) He had worked on social networking sites before (Note: founded Plaxo, which reached 20M users; early adviser to Friendster) and accumulated important insights.

After Facebook opened up their platform, Mark Pincus quickly seized the opportunity to start a social games company, Zynga, and captured the largest dividends. He was able to do so largely because he had worked on social networking sites himself. (Note: founded Tribe.net, invested in Facebook, Friendster, etc.)

During our conversations, Wang Xin made an important observation. Tracking the people who participated in the social networks waves in the U.S., some people did very well professionally and others less so. They can be divided into two groups - one group of people participated in Social since the beginning and eventually benefited, while the other group also participated from the beginning but didn’t benefit in the end. The difference is that the former group usually started in Silicon Valley and stayed there - they have never left the social networks entrepreneurial circle. As a result, they could catch the next Social trend promptly and also gather the correct insights.

That’s why I say as long as you can make sure that your company doesn’t die, the sooner you enter the market, the better. Because the earlier you enter the market, the more correct insights you can accumulate, and the more likely you are to be able to seize new opportunities.

Don’t say, “Guys, now the opportunity comes, let’s make it big.”. Chances are, you will flop.

Say, “Guys, I believe this industry will become big sooner or later, we just keep at it until the industry succeeds.”

Find the article insightful? Please subscribe to receive more learnings from Chinese Internet companies and I’d appreciate it if you can leave a comment or help spread the word!