#003 - Product Management Lessons by Meituan Co-Founder - Pt 3: Network Effects

Shape, Scope and Coefficient of Network Effects

👋 Hi! I’m Tao. As I learn about building products & startups, I collected some of the best content on these topics shared by successful Chinese entrepreneurs. I translate and share them in this newsletter. If you like more of this, please subscribe and help spread the word!

Let’s get you up to speed:

Wang Huiwen is the co-founder of Meituan, who recently retired at age 42 with an estimated net worth of >US$2B. He opened a Product Management course at Tsinghua University in September 2020. This article and others in this PM series are my translation and edits based on a compilation of the content of his course shared online. You can see other articles in this series here.

Network effects is the law of universal gravitation in the business world. Wang Huiwen defines it as:

As the size of the business (sales, #users, #customers, etc.) gets sufficiently large (vis-à-vis competitors), it creates significant advantages in:

User Experience

Cost of Production

(Note: A popular definition from Silicon Valley VCs - Every new user makes the product / service / experience more valuable to every other user.)

Two corollaries:

Different businesses have different network effects. Some businesses are destined to be small due to the lack of network effects.

In the same competitve market, the first to correctly identify and effectively leverage the levers of network effects will most likely to get network effects working in their favor and thus win the market.

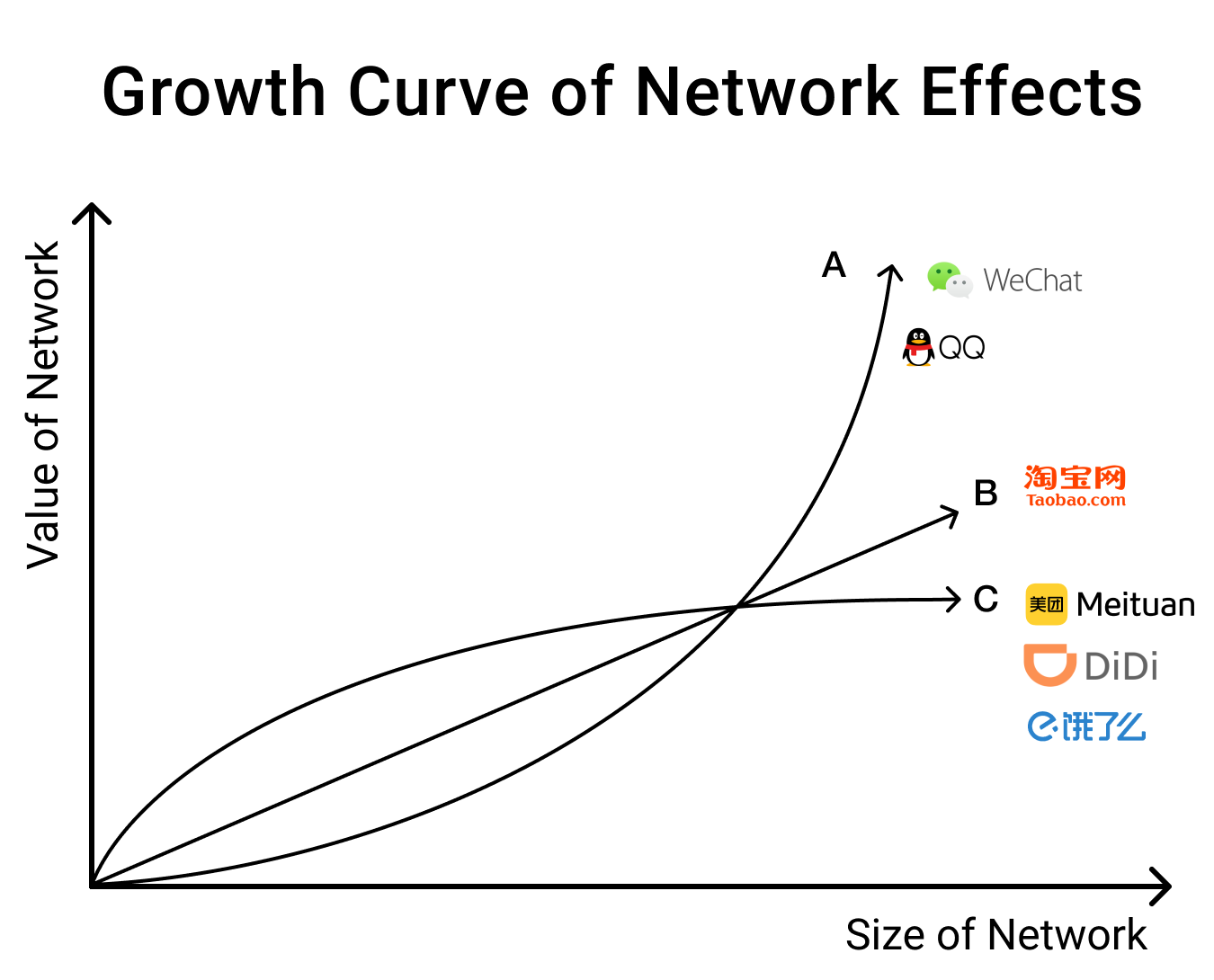

I. The Shapes of Network Effects Growth Curve

A. Exponential Growth

Curve A represents the most classic type of network effects - the value of the network grows in proportion to the square of the number of nodes on the network.

(Note: Metcalfe’s Law, V = N^2, mathematically the #links that can be formed between nodes. Or Reed's Law, V = 2^N, if there are subgroups to be formed within the broader network).

Examples: the Internet itself, social networks.

How strong network effects are present determines the eventual size of the business and whether it would still have competitors toward the end of the competitive cycle. WeChat is one such example - its network effects are so strong that it doesn’t have any meaningful competitors; it’s in a winner-take-all market.

Of course, there are also other instant messagers in China, such as QQ (also owned by Tencent). For that, we have to consider another dimension. The demographics of QQ users (Note: Mostly teens, high school friends, and online friends who only know each other on a pseudonym-basis) and their behaviours are fundamentally different from those of WeChat users (Note: People who exist in your phone address book - friends, family, co-workers, etc. It also allows pseudonym-based relationships). The cultural barriers between these two groups of users result in two separate social graphs, each in a different market solving different social needs.

The important thing is for the network to reach critical mass.

(Note: Critical Mass refers to the point at which the value produced by the network becomes greater than the value from the product itself, and of competing products - NfX)

B. Linear Growth

For curve B, the value of the network grows in proportion to the size of the network. (Note: Sarnoff’s Law, V = n).

Curve B describes e-Commerce plaforms like Taobao. Taobao can serve every additional new user, and the value of Taobao increases a little. But among users, there’s not much connection to be formed. As such, the value of Taobao grows linearly.

It helps to explain why even after being in the business for close to two decades, Taobao faces more and more competition (e.g. PingDuoDuo, Perfect Diary etc). Even with Taobao’s dominant market share, new entrants are still coming in every year - it shows that there aren’t strong enough network effects for the market leader to create a huge lead in costs or user experience to fend off new entrants.

It’s the same for food delivery. We at Meituan have worked very hard in this business, but Ele.me is still around. Our products have become highly homogenized. Even so, there are still two players in the industry - so the network effects aren’t very strong in the food delivery business.

C. Asymptotic Growth

As the network grows, after a certain size, the marginal growth in value of the network diminishes. Typically, networks with this type of growth curve are 2-Sided Networks (Note: Networks with 2 types of heterogeneous nodes, e.g. buyers & sellers, drivers & passengers, developers & users, etc.) with negative Same-Side Network Effects.

Not all 2-Sided Marketplaces have negative competition on the same side of the network. For example, Taobao’s supply approximates to infinity - each shopper buying an item doesn’t affect another shopper’s purchase. For ride-hailing, however, each passenger affects other passengers in his/her proximity negatively, same on the drivers’ side as they compete for rides.

For asymptotic network effects, after the network reaches a certain size, there is minimal improvement in user experience or costs reduction. Use food delivery as an example, having 1,000 delivery drivers vs. having 100 near you doesn’t reduce your wait time much. Consumers have a baseline expectation, as long as you meet that expectation, it’s fine - any faster would not make them much happier.

(Note: related reading - The Network Effects Bible)

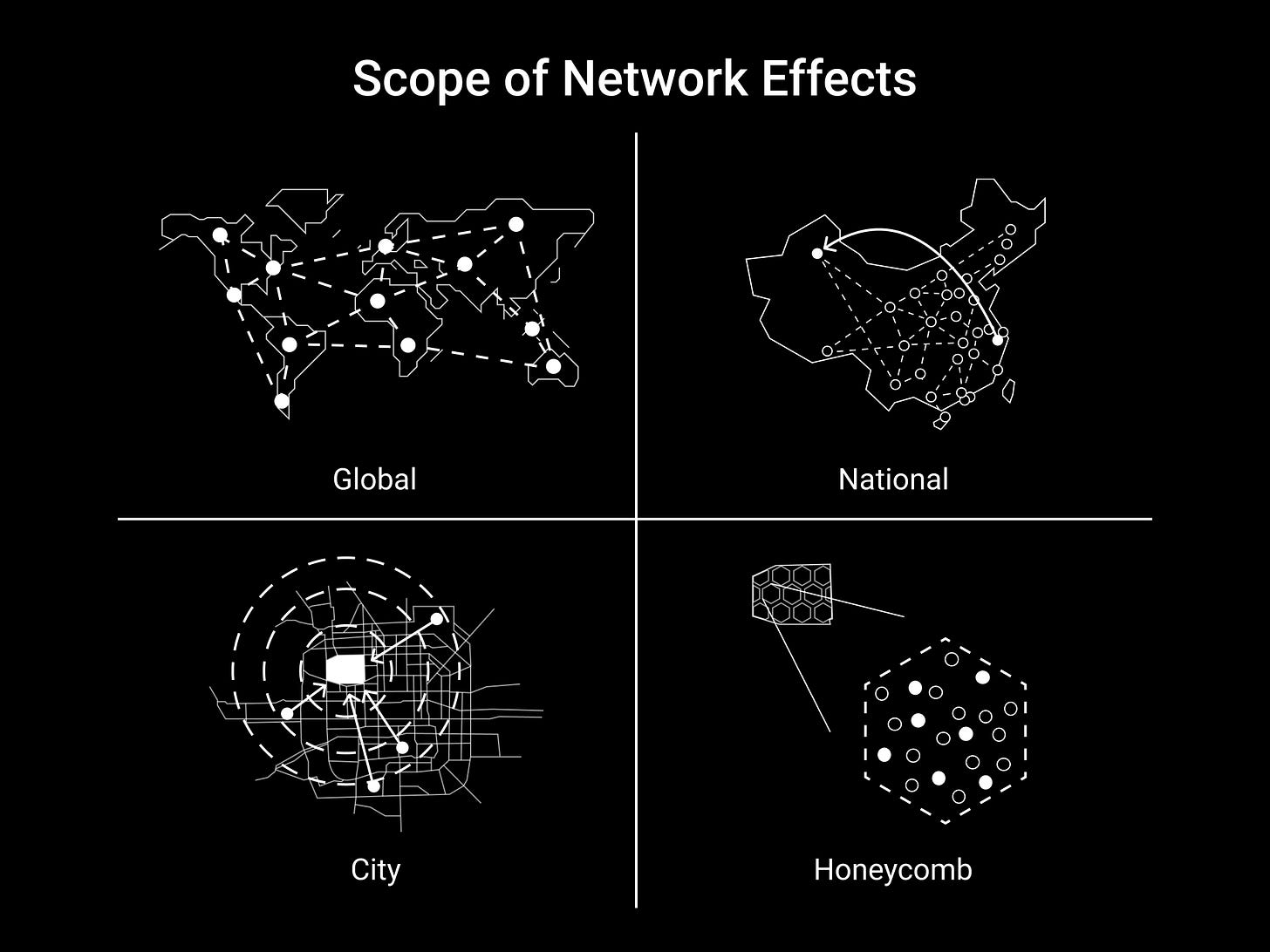

II. The Scope of Network Effects

The shapes of network effects growth curve describe network effects longitudinally. The scope describes their effectiveness geographically.

Global

Anyone in the world can participate in the network and the value created by having a new user on the network propagates throughout the global network. Examples include WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger. WeChat too, but it’s limited by language and cultural barriers. (Note: Language has network effects too). Even so, the United States wants to ban it - it shows you how powerful and important it is to have global network effects.

National (Regional)

Taobao best exemplifies national network effects - a buyer in the inland city Ürümqi, Xinjiang can buy goods from the coastal province Zhejiang (Note: a manufacturing hub in China). So for e-commerce, it’s impossible for you to acquire then defend the market in a city or an area - it has to be an all-out war with Taobao all over the country. That means burning cash all over the country, so the barrier to entry is very high.

City (Local)

Examples: ride-hailing, group buying.

You can group buy a nail service or a game of laser tag in the central shopping district in your city, and you may even hail a ride to get there. These services operate on a city level.

Honeycomb (Hyperlocal)

Example: Food delivery.

The small scale and highly localized nature of the honeycomb structure make it very hard to defend your competitive position. A honeycomb for food delivery (e.g. a university town), let’s say generates 100K GMV a day, it won’t cost much for your competitor to pay its way to acquisition for such a small geography.

The honeycomb scope determines the asymptotic shape of the curve - the network effects are limited. A well-executing competitor can throw money at the target, unit by unit, cluster by cluster.

Similarly, it’s also very hard to go on the offensive for city or honeycomb scope businesses. Even if you’re the market leader, to win over your competitors’ turf, you still have to fight in the streets, one block at a time. So the competitive cycle for such businesses is very long.

For example, Meituan started the group buy business in 2010 and we became the market leader in 2011. Many competitors died once they ran out of money. Even so, until 2014, we still weren’t the market leader in Xiamen city. Network effects for group buy work on a city level, and some smaller, niche platforms in Xiamen owned the relationships with merchants and consumers on their platforms.

(Note: related reading - Markplaces & Scalability: Lessons from Uber and Airbnb)

III. The Coefficient of Network Effect Growth Function

The shape and scope still don’t define network effects exhaustively. Even for networks with growth curves of the same shape, there is a coefficient to the function that affects their growth rate.

Up until early 2008, MySpace had more users than Facebook. (Note: MySpace peaked in April 2008 with 75.9 million monthly unique visitors vs. Facebook had 50 million in Oct 2007 and 100 million in Aug 2008). The logical conclusion based on what we’ve discussed so far is that the bigger network wins. Well, the size alone doesn’t determine value, the other factor is the level of activity in the network.

For every new school that they expanded to, Facebook studied how users behave on Facebook vis-à-vis on MySpace. What they discovered was that, for every school, Facebook had a higher user activity level that MySpace did.

The fundamental difference between MySpace and Facebook is that, MySpace is social network for strangers who use pseudonyms while Facebook is for real-life friends who use their real identities. The links that nodes form on Facebook are real-life friendships.

There are network effects in both networks, but there is a significant difference in the strength of their network effects. Whether Chinese or American, social networks for strangers have done poorly.

(Note: As people get comfortable with using their real identities online - through intentional efforts by the platforms (covered in Part 1), anonymous or pseudonym-based networks lose out to real-identity-based networks because people would become more and more invested over the long term in maintaining and growing their online presence and online network, as they would in growing their reputation and standing in real life, see Does Real Identity Matter for Networks?)

One final thought, management is anti-network-effects. Why do companies still expand and manage so many people? The business itself has network effects and the strong network effects from the business more than offsets the anti-network-effects from the management.

Find the article insightful? Please subscribe to receive more content like this and I’d appreciate it if you can help spread the word!

Can you elaborate on your final thought? What do you mean exactly with "management is anti-network-effects"?

And another observation, seems that Wang Huiwen is quite wrong with this line: "Whether Chinese or American, social networks for strangers have done poorly."

TikTok, Douyin, Kuaishou are the biggest social networks right now, surpassing Facebook and Instagram, and it focuses primarily on strangers. The takeaway is perhaps "content is king", and the issue of whether the content is from friends or strangers becomes irrelevant as long as the content can hook people.