#24 - Product Management Roadmap

22 min read

Apologies for the unannounced hiatus. I’ve been busy building my product.

I’m recruiting some users for a private beta test for my product. In short, I’m building a product that curates the highest signal-to-noise ratio tech content from the web and offers a distraction-free reading experience. It’s for founders, investors, product managers, and operators. If it sounds interesting to you, you can sign up here. It’s free. I’ll let you know once it’s ready.

On with the content. Wang Huiwen is gonna talk about Needs next. For Chinese product managers, they do it somewhat differently than in the West when we talk about solving people’s problems or making something people want. They think very deeply about it, almost on a philosophical level. That’s why I decided to publish this Product Management Roadmap first so you can see where Needs come in in the big picture.

Product Management Roadmap

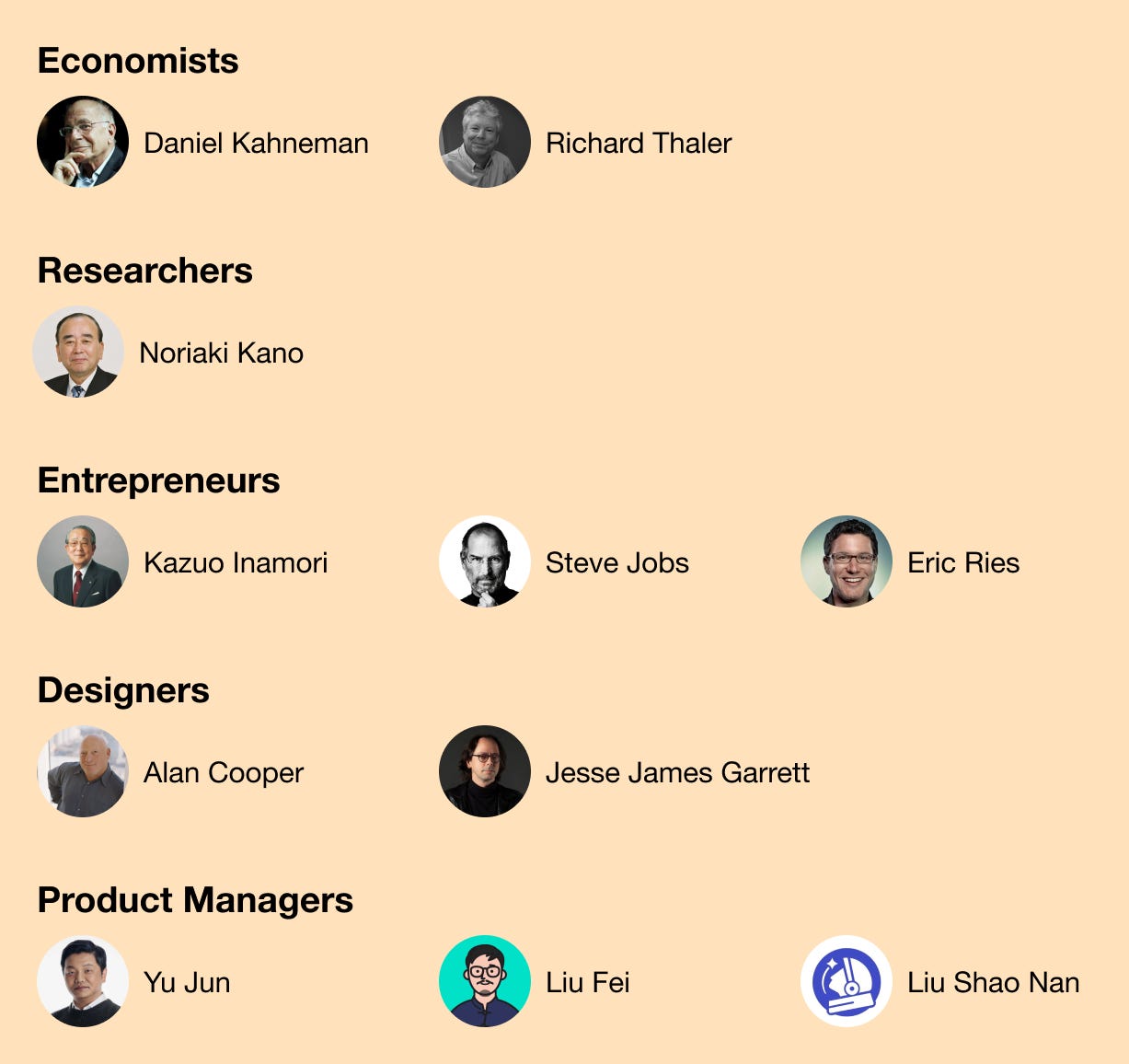

This roadmap is made by two Chinese product managers - Liu Fei (刘飞, WeChat Official Account: liufeinotes 刘言飞语), who wrote a best-selling book on product management and used to work at Didi; and Shao Nan (少楠, WeChat Official Account: southennanmu 产品沉思录), who writes great content and works at DXY.cn (a content & online community for healthcare).

Below, I’ve translated some of their discussion on this roadmap on their podcast.

I’d say it’s heavily influenced by the school of thought of Yu Jun (product leader at Didi, ex-VP of Product at Baidu; top 2 product guys in China, the other one being Allen Zhang of WeChat). I’ll cover more of him in the future.

(If you want a high-def PDF version of this roadmap, share this newsletter on Twitter/Linkedin/Facebook or with your friends/colleagues via Slack, etc, and send a screenshot of the share to chinaplaybook@substack.com)

Understanding the Users

Needs Analysis

Value Analysis & Product Design

Product Iteration

Interdisciplinary Knowledge

Legends

Podcast Discussion Transcript

Overview

Liu Fei:

First of all, let me briefly summarize the product thinking roadmap. It has a few modules. The first big module is Understanding the Users, it's strongly connected to Needs Analysis - your analysis has to be based on real users' needs.

The Product Design module follows because you design your product based on those needs. In between Product Design and Needs Analysis, there's a module called Value Analysis.

Similarly, Value Analysis is strongly tied to Needs Analysis. In short, needs are the problems that you unearthed from the users and values are the solutions from a product point of view to see if you can solve those problems for your users.

And Product Design is, okay, now I have some clear ideas on how to solve those problems from them, how do I put them on paper or screen? How would the ideas look like in a product, like an app for example?

After we've designed a solution, the next part is Product Iteration.

What I understand as the workflow of a product manager is roughly these few parts.

At the bottom, we have a few complementary appendices.

The first one is Interdisciplinary Knowledge. When I first got into the industry, and I guess you probably experienced the same, everyone didn't have much concept on interdisciplinary knowledge. But over the years, you started to hear more and more people talking about that regardless of which discipline you came from, you should be learning from other disciplines, especially from economics, sociology, psychology, etc. Right?

As for the other two appendices, one is the PM Career Development, which is quite simple and should be self-explanatory; the other is the Core Abilities of a PM, which is closely related to career development.

So, this is the overview of this roadmap. At first glance, are there any differences from your product system?

Shao Nan:

Well, first of all, here's what I find interesting about this map. I see this map as two halves. I used to buy a paper map whenever I go to a new city. For those maps, the actual map is at the center of the page, then you have sites of attraction at the periphery - which bus to take to get there, what are the local delicacies, etc.

So, the first half is the essential stuff, the core workflow. The second half is the attractions that make your journey more enjoyable, and info to make sure that you don't get lost. That's my first reaction.

Back to the product roadmap, for the Understanding the Users part, you and I are highly consistent, no difference there. However, I missed a whole module, which is the Value Analysis. I have not much concept. I probably have done some work in this area before, but I didn't have a formula or have abstracted it as a knowledge module. I'll have to think about it seriously. So that's a knowledge gap on my part.

On the other hand, for Product Design, I'll probably add something more to it, which is Service Design.

Yeah, because at that time, I found that, hey, a lot of experiences are not done on the phone. They’re separated from the pure app experience. For example, you have to negotiate with offline merchants, and you'd have things like third-party transactions. So I'd have to put a lot of thought into Service Design.

Liu Fei:

Right, ok, so the presentation is not what we traditionally think of as the product.

Shao Nan:

Exactly. It evolves with time, right? In the early years, the pure app experience might be enough. Looking forward, our knowledge now may become anachronistic in the future. That's why I'm like, how fun, same map, but what people see are different.

How the map came about

Liu Fei:

I'll talk about how my product thinking framework came about.

First of all, this map is not terminal and it's not a standard. Not everyone in the industry needs to agree with this or reference this. It's just my personal understanding. From a space perspective, this map is just one man's viewpoint. From a time perspective, this is just a summary at this juncture. I may add, delete, modify in the future. With that out of the way, I can talk about how I gradually came to this model.

When I first got into the industry, my first job is at Smartisan (a smartphone manufacturer). At Smartisan, I think I had some level of knowledge and understanding of the user. But not as complete compared to now.

The knowledge and understanding were more restricted to the user scenario or the very detailed minor points about a user, not the complete profile or mentality of a user.

It was like, I have a feature, I think about whether the users will like the feature or under what scenario the users would use the feature.

So this is a rather microscopic understanding. Yeah, so on the micro understanding, I was on the right track. But I severely lacked the macro understanding.

Of course, that was also due to the circumstances we were under. We didn't have the resources to conduct a lot of user research. So we didn't have the macro kind of understanding like who are the users on our platform, how do they live, what are their mental states, what's the distribution like across different demographic segments, would this group of users like this feature, etc.

We didn't do any sort of analysis, but maybe the deeper understanding of the users can come from actual practice in the Product Iteration module.

So my understanding at that time lacked this chunk. My core understanding was just starting from micro and design bottoms-up. Indeed, it was also starting with the users, designing the feature based on the user scenario. But the path in the middle is very simplistic - you have a scenario, the users need it, make the feature. Yeah, that was my product framework, it's so basic, a very short path.

Shao Nan:

We all started like that. At least, you had some concept of the user. When I started, we were building iOS apps, around 2010. Only at that time, I started to have this notion that oh, I'm making a product.

The methodology was just "the light bulb moment". Let's make a thermometer. Let's make a date countdown feature. Let's make a calendar... It's all starting from the self, giving zero care to who the users would be.

Just now you mentioned micro understanding. It reminded me of a user research case that left a deep impression on me. When I went to Baixing (a classified ads site), I think we all had some concept of the user. But all the methodologies that we used at that time were borrowed from advertising companies.

Liu Fei:

How so?

Shao Nan:

For example, like methods used by Unilever, the FMCG industry, such as focus group.Of course, they have many methodologies, but they're not suited for the tempo of Internet companies or the customer groups they serve.

For example, the users of Baixing would be the relatively lower-income groups. When you invite them to the building for customer interviews, you couldn't get really get anything out of them. They were dumbstruck with the fancy offices. Ask me anything, whatever you want, I'll tell ya.

Liu Fei:

Got it.

Shao Nan:

Yeah, so I remember clearly this uncle, we needed him to pay for something. To pay, you need to install a plug-in on IE (Internet Explorer). The uncle says, “okay, I can pay.”

We were standing behind him like, why didn't he click the button, why didn't he click the button. And the uncle started to sweat because of all the stress. He wiped his forehead and said, “don't worry, I can pay.”

After struggling for 10 minutes, he finally gave up - “sorry, I can't pay.”

Liu Fei:

He treated it as a task. I have to complete it. It's completely different from his normal living state.

Shao Nan:

Right. We've talked about Interdisciplinary Knowledge. When the Internet industry was just starting, we vaguely know that we should be doing user research, but we could only borrow experience from other industries since we've never done it before. We borrowed focus group. We borrowed eye-tracking. Wow, eye-tracking right, so advanced. But it's useless, haha.

So I feel quite deeply on this understanding the users part. As compared to before, our methodologies really evolved a lot.

……

Shao Nan:

Then what happened for you?

Liu Fei:

As mentioned, my product thinking was a very short path at my first job - I discovered a scenario or need, then boom, we have this feature.

Since that time, and actually part of the reason why I left, I started to have some sense about Internet products. Whether it's the experience at Smartisan, or conversations with friends who work in product, or even observations from what people shared online, I started to feel, hmmm, people build products differently, and I wanted to experience other ways of building products.

That's why I went to a more operations-driven industry - on-demand nail services - and started up. Afterward, I worked in food delivery and ride-hailing, and the understanding deepened more and more.

However, at the time when we were starting up in nail services, I reflected retrospectively, I was only more aware of the early parts of the map - users and needs. But even for users and needs, I didn't analyze very well and I had some misconceptions.

For example, the understanding of the users at the time. My understanding of the users are just the customers of nail services. I didn't know much about the nail technicians.

I thought they were not the users. They were not under the purview of a product manager. You know, we pay them and let them go to the place to serve. Really, no kidding, my understanding was really that shallow.

Of course, if you think this way, you wouldn't think too much about the needs of the two parties on a marketplace, the match between supply and demand... and consequently, your understanding of user experience would also be very shallow.

My understanding of user experience is just like those early UX-type product managers - whether the app looks nice, has cool visuals, how are the interactions, etc.

Of course, on-demand nail service is the experience of the full process. Your product in fact is the entire service from start to finish, not the app. If it's the entire service, then some key issues with regard to services, such as punctuality, the quality of the nail services, the service attitude of the technicians, etc. become core product points.

If you only care about the app, then you only care about the pre-order experience. But in fact, the pre-order experience is relatively unimportant. What matters more is the after-order experience - how you dispatch orders, how to improve nail technician's service quality, how to manage them etc.

Of course, I only learned this later on. When I was starting up, my understanding was really simplistic and shallow.

Shao Nan:

That realization came about pretty much around the same period for both of us.

Here I want to interject an interesting story. In the early days of Airbnb, they have something called Project Snow White, I've specifically studied it.

At that time, the two founders felt it was very difficult to make any progress because booking an Airbnb is such a complicated user flow. Say I'm going to rent my house to you, where should I put the keys, right? What should you say when you enter the house? What shouldn't you say? It's so complicated. Users don't know what to do.

Of course, we all started at the same line. The founders are also designers, and they had never done a service business before.

Later, the founders went to Disneyland and they found that, wow, the experience is so nice here. That's when they realized that a lot of experiences are not done within the "product". They're done outside the "product".

Once they realized that, they started to think well, how does Disney develop their cartoons?

If you've studied animation or film, you know they have something called the storyboard. That's how they outline a story. For example, today this person goes out the door, turns right to unlock his bicycle, rides the bicycle forward, etc. You have a camera language.

So after they came back from Disneyland, the Airbnb founders hired a Pixar illustrator to draw out the personas of a few typical users. For example, a poor student, an old couple, a rich person with 3-4 houses, etc. Draw these people out on paper, these are the User Personas. That's when I first learned of this thing called user personas.

The second thing you need to do is, you have to tell a story. For example, what's the poor student's story? Right, I'm a poor student, but I want to travel to Europe, and I don't have any money. Maybe I can rent out my house and let it earn money for me, while I travel in Europe?

So this is the student's story. The illustrator then started to draw, maybe 15 - 20 frames. With the frames, the scenarios become very clear. For example, when I meet the host for the first time, should I bring a gift for courtesy and rapport, right?

When the host writes the introduction for the house, since the guest is here to experience local life, he should probably tell the guest what's good to eat around here, what fun places, which area in Brooklyn that you shouldn't go to, etc.

This kind of thing you can never think of looking at a screen. Is this how you felt when you came to that realization?

Liu Fei:

Yes, it's very similar to my journey. Actually, the first phase was, I found that the product or the app didn't seem to matter a lot. I was feeling rather depressed. Like, wow, product managers don't matter in this business.

The second phase was when I started to realize, oh, this bigger thing is the product. Product managers don't just need to work on the app. If you have thought through how to solve the various problems through the product, then you've graduated to become a mature product manager. So the second phase was the enlightenment.

……

Liu Fei:

Yeah, you know, we all know these words at the time. Users, needs, scenarios, values, we know them. But in fact, our understanding of these concepts, and the methodologies that are based on them, we can only say we had a very superficial understanding then, or our understanding was problematic. It wasn't until later as we did more work, then we started to have a clearer understanding of these concepts. It's a cognitive process. So I'm thinking, for some junior PMs or newbies, they look at this map, and they'd think, it's not that difficult, I know this, I've heard of these things.

To really understand it, you have to be making products and participating in the operations to have a visceral appreciation.

The Answer is in the Field

Shao Nan:

Right. Actually, I have a training method. I was trained this way as well. When I first went to Baixing, one of the things that we needed to do was to conduct user research via phone interviews. That's no methodology, and no one to teach you. You just need to talk to some people today. What do they not like about our website?

You know, the first time I picked the phone, my hands were shaking. Like, what do I even say to this person? You don't know whether it's a man or a woman, old or young, you don't know anything. It's just a number.

But anyway, it's an excellent way to train how to understand users.

Here's my view, some people may not agree. Some people say, okay, I know how to conduct user research. But they've only ever sent out surveys or looked at usage data, or even observed people from afar. I'd say it's not on the same level as talking to the user 1-on-1, trying to understand his motivations, his concerns, etc. It's like kung fu, you have to put in the work.

Liu Fei:

I always tell the younger PMs around me, the best way is you have to, have to be in the field, or you interact with the users directly. For example, if you're building a content product, the users just consume content. Of course, there's no point going to their houses. But you have to talk to them, observe how they consume content. This is the field. It doesn't mean you have to stand beside them.

This I have experienced deeply, especially after I worked on nail services, the times that I go on-site significantly increased.

When I was doing food delivery, my company started to have rules that you have to deliver food yourself. X orders a month. It wasn't that stringent. At Didi, it was even more stringent. We have to register as drivers and we have to drive X orders or have to earn $X amount. Of course, this is just for the driver-side PMs. For the passengers-side, you don't have this requirement.

For the driver-side, it's a strict requirement. If you don't know how to drive, you sit in the car. You have to be in the car. Especially in the later phase of the company, Mr. Yu Jun asked our driver-side PMs to have an entire day to drive on the road every month or every quarter. Why? Because previously it still wasn't authentic enough.

Some of us just drive for one order, two orders, during lunch break, whatever. You'd never experience the mental and physical states of the drivers under the real work intensity.

Under the driver's real work intensity, for example, after you drove for 10 orders a day, how's your energy level, your mental sharpness when you receive orders, and what's the chance of getting into accidents when you drove too many rides. Or if you're dispatched to somewhere really far, when this situation happens, you'd start to worry about how to take care of your next few orders of the day, etc.

When you actually care about your income and your number of orders for the day, that's the most authentic experience. That's when you can really discover a lot of problems that the drivers face.

Echoing what you said earlier, only after you spend enough time in the field, to actually experience the lives of the users, you can train your understanding of the users, and the understanding of the scenarios.

Previously I thought going to the field is not that different from having a phone interview. You get some users in the office, you ask them questions. It's not that different right? Actually no. I discovered that in the field, the amount of information you can gather is much larger.

For example, food delivery. The delivery rider gets the meal from the restaurant, goes on with the ride, arrives at the consumer's door, delivers the meal, then leaves. Isn't that a simple process? You go to the field, you also see him performing the same process. Isn't it?

No. When you're in the field, you’d find that, oh, for example, to get the meal, the restaurant may be crowded, and your delivery rider is squeezed there along with everybody else. There are other delivery riders trying to fight with him to get their meals first.

Or queuing, which happens very often. Or the restaurant prepares the meal too slowly. Or you have some disputes - his order is that, my order is this, who gets this dish? Or you have a poor internet connection, the order doesn't come out in the dashboard, how does the delivery rider communicate with the restaurant owner? Or the delivery rider found that he can't get this meal from this restaurant in time, but he's rushing to another place, how is he supposed to handle that?

When you're in the field, you'll encounter all sorts of problems and the amount of information is overwhelmingly big.

So I think, for me, only through experiences like this, I started to have a good sense of how to solve the users' problems. It started when I was doing nail services, but at that time, I only discovered the problems, I didn't know how to solve them. Only at Didi, this product sense was groomed well.

When I first went to Didi, I set a goal for myself that I'd spend an entire quarter to understand the drivers. I had become intentional in understanding the users, using the effective methodologies that I know of.

Shao Nan:

Yeah, I also felt that deeply. You mentioned food delivery, I also worked on food delivery. Some very simple things, like for the restaurant, when you have five riders coming in, you have to make sure they don't take the wrong order. Or you have to make sure you have a pair of chopsticks inside the package. If you forgot the chopsticks, for sure, it's a bad review.

Another point is that some people ask me why I don't believe in surveys. Because you'd have deviations. Then they say, if I have enough quantity, would that be okay? I think not. You can discover a lot more information being in the field.

A lot of people use surveys in the wrong way. I want to expand on this point.

They say surveys are good. You can have a large number of responses, and they can inform on some user behaviors. You go to the field, you can only see 3 or 5 people.

Well, on-site research is qualitative. I've seen people do on-site research for quantitative reasons, like doing 500 in-person interviews. You've completely missed the point.

If you go to the site, as we talked about, you can find out a lot of unexpected things, then you can think through those unexpected things and come up with solutions. Like poor internet connection. What's the probability of that? You can't be always offline right? Only in certain spots, you have a poor connection. So how do you deal with that? Or queuing at peak hours. Or your rider delivered the wrong order. Or your rider's vehicle broke down. Etc. These things are when you see the signs, you can see the patterns.

Of course, you don't just need to go to the field, you also need to synthesize diligently.

It's hard work going to the field. However, if you do this for 5 years, regardless of what industry you're in, or whether you changed job, you're just different from people who spent one year on-site.

I used to lead a junior PM. When he just came, I asked him to just do user research. He's been doing that for 3 years now. Now when I ask to him to conduct a user search, he said he'd just interview three users, and he'd tell me the insights that he gathered. When he first started three years ago, he'd call 20-30 people a day.

Three years back, his summary was superficial, like it's a female, 34 years old, why she uses DXY.cn (a content & online community site for healthcare).

Now he'd say, this is a mother living in a first-tier city. She's conflicted inside because her parenting ideology is very different from that of her parents. She craves recognition from people who can understand her position. But at the same time, she doesn't have that much money to hire a private physician or go to high-end clinics. What she wants is identity.

You see, it's the same person, just three years apart, the kind of user insight that he can get out are completely different.

Liu Fei:

It's about knowing the purpose behind these methodologies and how and when to use them. Like on-site that we've talked about, is to discover the problems and gather qualitative information. You know what questions to ask. Only when you know what questions to ask, and your questions are specific enough, can you qualitatively define the problem and the information that you gathered is valuable.

From User to Users

Shao Nan:

Right. Let's move on to the next question. You see our recollections were pretty similar, we both started not paying attention to the people. We initially just focused on the small behaviors, like what color of the button, and then shifted to start focusing on the person - the whole person or a few types of person.

When did you start to realize that this is still the individual(s) and move on to the group or the industry? Like for ride-hailing, you have the drivers, the car rental companies, the municipal governments, you know, interested parties. When did you realize that?

Liu Fei:

Right. As I mentioned, I realized that the product is this bigger thing when I was working on nail services. When I moved on to food delivery, I started to deliberately train myself in this area.

As for from individual user to the collective group, it should be when I was working on food delivery. That's when I realized I need to have a macro understanding. You need to have some judgments about what the industry is and where it is going. Who are the users within this industry? What's the logic that this industry operates on?

I think Mr. Yu Jun said it the best. It's just the matching between supply and demand. All the products that we use, are in essence transactions. Of course, that's a higher level of abstraction which I learned later.

When I was doing food delivery, I know that let's say you're doing logistics fulfillment, your upstream is the delivery platform, and your downstream is your riders. You deal with the merchants and the riders. Between these three parties, what role do you play?

What are the needs of the delivery riders? Why would they be willing to come onto your platform? What are the needs of the merchants? Why would they come onto the platform? Etc. So at that time, I started to have these concepts.

At Didi, of course, my understanding got even deeper. We'd think from the macro perspective. Like you mentioned, the drivers are one part of the supply. Supply, first of all, they face the consumers. There's also the participation of the platform in that process.

How do you get so much supply as a platform? You need to have a lot of people. Where do people come from? People, I'd give you a few examples. It could be the rental companies, or the small collectives, or even just a driver that knows a lot of other drivers.

The other question is the cars. Where do you get the cars? You need to partner up with a lot of car companies. What's the ecosystem around that?

Later on, you'd face government regulation. You have to deal with compliance. Or even where your car plates come from. Etc.

Slowly, you learn the underlying logic of the industry. From this underlying logic, you can further analyze a few layers. The logic for driver-passenger matching. The logic for orders dispatch. The logic for your service. Etc. From each logic, you can further discover a lot of problems.

So gradually, you start to have a map of the entire industry in your head. And you can locate where your part fits in on the map.

This is drastically different from when we started - I observed some minor user behavior, boom, I made this feature to fix that. We have a much longer path, and the solution would also be more complicated.

Interdisciplinary Knowledge

Liu Fei:

The central problem is that you won't be able to learn everything. Good product managers have a strong problem-solving mindset. What problem am I solving right now? What subjects do I need to know to solve this problem?

Previously at Didi, I was a platform-side PM, so I needed to learn a lot about economics, algorithms, and demand and supply matching. The demand and supply matching impacts the business, the ecosystem, and the platform. To balance it, we need to use some algorithms and implementation methods.

If I was working on service strategy, like my peers dealing with driver and passenger disputes every day, I had to study law. Every day they study law. They need to know how to make rules, how to enforce them, and even consider what would be the potential public opinion, what's justice, etc.

That's an important task, designing a feature when you need to consider public opinion. You can't just say it feels fair and reasonable to me, or to us as a platform. Because that's would be a black box. You have to consider how drivers and passengers would take it. You can't just be I'm doing right by my own values anymore. No.

(Only these points are translated due to the length limit. For me, studying this map alone is like a 10X product learning experience. I highly recommend keeping it somewhere close by and revisit regularly.)

👋 Hi! I’m Tao. As I learn about building products & startups, I collected some of the best content on these topics shared by successful Chinese entrepreneurs. I translate and share them in this newsletter. If you like more of this, please subscribe and help spread the word!

One of the most insightful pieces that I've read. The emphasis to be on the field is so on to the point. We need to know about our users before building anything for them. The defination of PM is also correctly pointed out as PMs need to solve problems via product.

I would just like to add a bit here, as PM job is not just to solve problems via product but also ensuring that the target users are using the product to solve the problem.

As many a times it happens that the product is able to solve a problem but the users are not using it (due to various reasons like complexity, doing things manually is more easy etc) and to me that's a failed product and the PM has not done their job.