#33 - Design: The Good, The Bad And The Ugly

24 min read - Is Taste Subjective; The Taste Gap; Principles for Good Design

Note: This is an article written by Shuo Yang in 2014. He’s been a designer and an entrepreneur and now works at Google. You can find him on Twitter here. Even though it’s slightly aged, the piece covered today is a central piece in my learning about design. It ties together some of the most fundamental design principles with a cultural context that I resonate with. More importantly, it’s encouraging. I hope you find it useful.

P.S. Long piece, best viewed in browser.

When you don't create things, you become defined by your tastes rather than ability. Your tastes only narrow & exclude people. So create.

- why the lucky stiff

A Designer’s Taste

1. Taste and Ability

The thing that a designer needs the most is good taste. When we say someone has good taste, we usually mean he has a keen eye for aesthetics or he is good at seeking out beauty. Surprisingly, when someone does have good taste, it's often not because he's particularly good at discovering beauty; it's because he's particularly good at recognizing ugliness. If he can see the ugliness, and he can't stand it, he’d naturally tend toward beautiful things.

Hence, having good taste is not just about beauty, it may have even more to do with ugliness. By “beauty” and “ugliness”, we don’t just mean how things look to our eyes, they also pertain to the beauty and ugliness of products, technology, systems, human nature, etc.

In the first couple of years when you start your career, especially for those of us who work in design, there may be a gap between your taste and your competence. Your work may not be as good as your taste would dictate. Don’t despair, for your skills would eventually catch up. Ultimately, it’s your taste that would determine your style.

Ira Glass, the creator of the hit radio program This American Life, shared with us his experience in an interview:

All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But it’s like there is this gap. For the first couple years that you’re making stuff, what you’re making isn’t so good. It’s trying to be good, it has the ambition to be good, but it’s not quite that good.

But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is good enough that you can tell that what you’re making is kind of a disappointment to you. A lot of people never get past that phase. They quit.

Everybody I know who does interesting, creative work went through a phase of years where they had really good taste and they could tell that what they were making wasn’t as good as they wanted it to be. They knew it fell short.

Everybody goes through that. If you’re going through that phase right now, you gotta know it's totally normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. Do a huge volume of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week or every month you know you’re going to finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you’re going to catch up and close that gap. And the work you’re making will be as good as your ambitions.

I took longer to figure out how to do this than anyone I’ve ever met. It takes a while. It’s gonna take you a while. It’s normal to take a while. You just have to fight your way through that.

- Ira Glass

2. What Determines Your Taste

One’s taste is shaped by various factors collectively. The most direct, perhaps, is the culture in which one grows up. What is Chinese culture today? Some field photographs from the (former) creative director of frog design, Jan Chipchase, may give you an idea.

One can’t help but notice the gap between wealth and poverty, the contrast between Western culture and traditional culture, and the distance between idealism and reality.

For people who grow up in such a diverse and divergent culture, it stands to reason that they’d be more tolerant of differences and their tastes more flexible. You can say that Chinese people are extremely adaptable. They take whatever comes their way, the good and the bad. They could drink poisonous milk and eat gutter oil.

You can say that Chinese people are influenced by the philosophy of the Doctrine of the Mean (中庸) — doing things the way most people do and don’t deviate from the natural order. The bird that pokes its head out gets shot.

You can also say that the Chinese are dialectical. (Note: Dialectical materialism from Marxism). If asked to compare two things, the answer you usually get is, “This one is fine, but that one is also not bad. Each has its own virtues.”

Because of the contradictory environment that they grow up in, Chinese people have to have a great tolerance for ugly things. Otherwise, you won’t be able to make it. In China, people who express discontent toward ugliness are often shunned, chastised, and may even risk their lives. As such, most of us involuntarily accept our surrounding world. Critical voices are few and far between.

Interestingly, the public doesn’t think of those things as ugly. Only when someone points it out, do they finally realize, yeah, it indeed is ugly.

From melamine milk, and gutter oil to the poisonous drug capsules now, they were essentially the results of people doing nothing in the face of ugliness. China needs more people who can't tolerate ugliness, and a re-education to recognize what’s “ugly”. We will then discover beauty by exposing ugliness.

3. Tolerance of Ugliness

iD Commune (Note: an industrial design-focused blog in China) published an article called “The Perception of Beauty”, and the section about “taste” strongly resonated with me:

Taste in our colloquial context is usually centered around style, like how we would describe someone who is particular about the way s/he dresses as “having a good taste”. If we were to evaluate Steve Jobs’ taste based on his wardrobe, it’d be a very narrow and misleading view of what taste really is. Taste is an ability, not a style.

(Note: Actually, Steve Jobs was particular about how he dressed. R.I.P. Issey Miyake.)

We need not be punctilious about the language. Conceptually, having good taste is definitely not as simple as dressing meticulously or following fashion trends. Taste is an ability to perceive beauty. It’s a power. And every one of us possesses this power. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have masterpieces that captivate entire masses.

If everyone has this ability to perceive beauty, then what sets Steve Jobs’ taste apart? It is because some of us have more of this ability and others have less? Personally, I think it’s the exact opposite. Steve Jobs’ taste stands out from the rest because he’s intolerant of ugliness, almost to the point of extreme. This critical standard had affected him his entire life.

When Steve Jobs moved to a new house. His new home almost had no furniture for a decade, because he couldn’t find anything up to his satisfaction. He’s someone that would prefer nothing than something less than perfect.

Therefore, the intolerance of ugliness is the best explanation for some people whose tastes stand out from others. It’s also an explanation for why China can’t produce people like Steve Jobs. Because we have been inundated with ugly stuff our whole life, we’ve become very tolerant of ugliness. Don’t believe me? Let’s take a look at these incredible buildings.

4. Is Beauty Subjective?

Growing up, we were taught that beauty is subjective. It’s in the eye of the beholder; it’s a matter of personal preference. There’s no wrong way to paint a picture. You can’t make fun of your brother for coloring people green. “You like to do it your way and he likes to do it his way”. Your mother at this point is not trying to teach you about aesthetics. She’s trying to get the two of you to stop bickering.

Saying that taste is just personal preference is a good way to prevent disputes. The trouble is, it's not true. You feel this when you start to design things.

If you’re a designer, and you buy into that beauty is subjective, then you can’t go about doing your job. If beauty is just personal preference, then why do we need to design? Everyone's is already perfect: you like whatever you like, and that's it.

Experienced designers would realize that as their gain experience, their understanding of beauty is changing. There are some beauties that transcend individuals. Seeking out the commonalities between these recognized beauties becomes the primary approach to how they work.

In high school, Karl Marx taught us to look at problems dialectically. Everything is relative, including truths. This notion sticks with us even as adults. Once you start to think about design comparatively, you will find that there are striking similarities in the ideas of beauty across different fields. The same principles of good design crop up again and again.

Principles of Good Design By Dieter Rams

If there is such as thing as universal beauty, naturally there would be ways to create beautiful things that appeal to the public. German industrial designer Dieter Rams spent decades answering his own question - is my design good design? - and put forth his ten principles for good design.

Dieter Rams talked about design in the context of industrial design, which is the art of shaping manipulable products. In his context, design objects include all kinds of physical things that people want, from cutlery to chairs, telephones to cars. I will not discuss the differences between industrial design and other design fields here, nor will I go through Dieter Rams' ten principles one by one. I’ll just pick a few that I find interesting to share.

5. As Little Design As Possible

Another way of saying this is that “good design is simple”. You may have heard different versions of this many times in other fields as well. In mathematics, the simpler the equation, the shorter the proof, the better. For architects, it means focusing on carefully chosen structural elements, not excessive ornaments. Similarly, in writing, it means “omit needless words”, “brevity is the soul of wit” and “write a shorter letter”.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who succeeded Walter Gropius as the director of The Bauhaus, a ground-breaking school of modernist art, design, and architecture, popularized the design philosophy of "less is more" in architecture. When modernist architects try to create buildings that abandon the ornamented traditional styles, they unconsciously designed buildings that still had ornamentation. Only when space and articulation replaced symbolism and ornament as keywords in architectural conversions, did good buildings begin to emerge.

John Ruskin believed that the soul of architecture was contained in the veneer of decoration that concealed the exterior walls. I think it’s fair to say today that you can have ornamented buildings, but don’t build buildings that are ornaments.

In fact, most things are inherently simple. We incessantly stress “less is more” because when doing design work, most people forget. For example, in web design, some people fear white spaces and always want to fill the page with bells and whistles. It’s actually quite stupid.

The design embellishments are just a diversion to cover up the lack of substance. When you force yourself to make things as simple as possible, you are forced to face real problems. When you can't cover up with ornaments, you have to do essential parts really well.

6. Good Design Is Timeless

In math, every proof is timeless unless it contains a mistake. This is why mathematician G.H. Hardy claimed, “there is no permanent place in the world for ugly mathematics.”

Aiming at timelessness (or at least long-lasting) is the best way to make yourself find the best solution to the problem. If you don't want your product to be replaced, then you have to make the best possible one. This is why the works of the great masters are compelling in any era and leave little room for those who came after.

In a similar vein, aiming for timelessness is also a way to avoid the undue influence of trends. Trends change - every year, every season, or even every day. If you want to make great products, you should avoid being controlled by what’s hot right now. Take Samsung and Apple as an example. Samsung is clearly a trendy company, it follows its customers’ needs closely. Whatever consumers want, they make. Apple is more concerned with making great products. They do not necessarily listen to everything consumers have to say. They don’t care about what’s popular. They care about finding the right answers.

If you look at the entrepreneurial boom in China, many startups are pursuing the current hottest trends (Note: 风口, fengkou, “Wind Gap”), often copying the latest hits in the United States.

New Internet concepts spring up almost every day. LBS (location-based services), SoLoMo (social-local-mobile), Cloud Computing, Pinterest, etc. The media hype has not only failed to inform, but has misled many entrepreneurs to think that if they had found a hit idea, they’d definitely be able to make it big, and users would flock to their app.

Reality suggests otherwise. Whether it was the previous center-of-attention group buying, or the explosively popular social game "Draw Something", they were all fads that slowly faded away from our lives over time. On the other hand, if something is long-lasting, its appeal must come from its own quality, not its popularity.

If good design is timeless, then how do we judge whether or not our work is affected by time?

One way is to make your work appealing to multiple generations of people. It’s difficult to predict the future, but one thing is for certain - the people of the future will not care about our fashion today. Teenagers today don’t care about their parents’ or grandparents’ fashion. It’s also true in the reserve. Your grandma doesn’t care about what kids are doing nowadays. If your work can appeal to people today as well as people 200 years ago, chances are it will still appeal to people 200 years from now.

7. Good Design Makes A Product Understandable

Good design makes products easy to understand. Many a designer worked very hard only to discover their efforts had been in vain because they focused on the wrong problem.

Use typography as an example. With the influence of the Bauhaus Movement in the mid-20th century, after the birth of Modernism, there was a boom in the usage of sans-serif fonts. This movement continued to even now. Designers everywhere in the world just slap the Helvetica font on everything they touch, because the sans-serif fonts look clean.

(Note: Sans-serifs fonts reign supreme today, as shown in below Twitter thread.)

However, whether having the serif or not (Note: in other words, aesthetics) is not the primary concern of typography. The primary concern should be legibility (i.e. effective communication). They should make content readable. Times New Roman is a serif font that’s easy to read. And there are many great serif fonts like it, such as Garamond, Baskerville, Carlson, Egyptienne, etc.

Great products are “thorough down to the last detail”. Even the most unnoticed details such as choosing the right typography require lots of research and comparison. To find the right fonts, the designers of the news reading app, Prismatic, studied the history of the various types of fonts and their developments, conducted a thorough analysis of the pros and cons of the specific candidates, and tested the fonts against their data:

Garamond is a French old-style type design from 1530 that was forward-thinking in geometric proportion and balance in stoke. Still, it had some imbalances, like the lowercase “a” and “e”.

Egyptienne, which is based on the Clarendon model, pairs really nicely with modern sans-serifs.

The varying thickness of the strokes and their balance in serif fonts work similarly to Chinese calligraphy. In good calligraphy work, the strokes are definitely not uniform. They are dynamic, in an overall balance. The human visual perception naturally creates an aesthetic response toward the interweaving of lines of varying thicknesses. Below, is a work by Piet Mondrian in the Neoplasticism Movement. The intersecting lines have varying thicknesses.

If we were to change the lines to the same thickness, the piece loses a lot of character immediately.

Sans-serifs are not all bad. They look great as article headings. What’s sad is that most designers probably don’t know any other sans-serif fonts other than Helvetica. There are many good sans-serif fonts, such as Akzidenz-Grotesk and Univers.

Akzidenz-Grotesk, created in 1898, is influenced by many fonts that come before it - Baskerville, Garamond, Carlson, Didot, etc. Akzidenz takes their geometric proportion and balanced strokes to a whole new level, and drops the serifs. Contemporary versions of Akzidenz-Grotesk descend from a late-1950s project to enlarge the typeface family. These efforts to achieve a more machined yet human feel led to Helvetica from Max Miedinger, and the works of Adrian Frutiger, like Univers.

Typeface design started with the invention of printing. Europeans claimed that printing was invented by a German named Johannes Gutenberg in 1450. Little did they know at that time that Bi Sheng in China had already invented movable type printing centuries earlier in 1040, as recorded in Dream Pool Essays by Shen Kuo.

The writing of Chinese characters has always been an art form known as calligraphy. Its influence spread throughout East Asia. However, Chinese today who write Simplified-Chinese barely retain the ability to appreciate calligraphy. We failed to inherit the historical developments in typography from our ancestors. Today, the Chinese fonts on computers are awfully scarce as compared to other languages. It’s a damn shame to lose our traditional culture like that.

![Uboku Nishitani, Koyagire Daiishu [The First Seed of Koyagiri], vol 17 of Shodo Giho Koza [Techniques in Calligraphy] (Tokyo, 1972) (Image from Envisioning Information by Edward Tufte) Uboku Nishitani, Koyagire Daiishu [The First Seed of Koyagiri], vol 17 of Shodo Giho Koza [Techniques in Calligraphy] (Tokyo, 1972) (Image from Envisioning Information by Edward Tufte)](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!m74H!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa5551b49-0286-4cd4-aaf5-f815ba89d828_800x1005.jpeg)

8. Good Design Is Honest

An honest product does not make false claims or exaggerations. To a lot of folks, honesty and design seem to be at odds with each other conceptually. But the importance of honesty in design cannot be overstated.

Take for example the data charts that we see everywhere being used for justification and something we automatically ascribe credibility to.

If you believe that a piece of data or a chart is the most powerful, indisputable evidence - after all, “data doesn’t lie” - then you’re mistaken. Charts do lie. The father of information design and data visualization, Edward Tufte, said in his book, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information:

When a chart on television lies, it lies tens of millions of times over; when a New York Times chart lies, it lies 900,000 times over to a great many important and influential readers.

An example in his book is a chart that shows the change in traffic deaths due to stricter enforcement by the police against cars exceeding the speed limit:

Nearly all the important questions are left unanswered by this display:

A few more data points add immensely to the account:

Imagine the very different interpretations other possible time-paths surrounding the 1955-1956 change would have:

Comparisons with adjacent states give a still better context, revealing it was not only Connecticut that enjoyed a decline in traffic fatalities in the year of the crackdown on speeding:

In short, the same chart can be used to convey a lot of different meanings. Finding the best way of communicating information with integrity is the work of the designer.

Paul Graham’s Principles for Good Design

The co-founder of Y Combinator, Paul Graham, outlined his principles of good design in his essay, Taste for Makers.

(Note: Since we’re translating back to English, I thought I’d just quote Graham’s words directly when appropriate since he expressed these points with better precision, efficiency, and style. PG’s words are in italics.)

9. Good Design Is Suggestive

Literature works can be described as either descriptive or suggestive, as do paintings. Suggestive works usually engage people more than descriptive works.

Everyone makes up their own story about the Mona Lisa.

In architecture and design, this principle means that a building or object should let you use it how you want: a good building, for example, will serve as a backdrop for whatever life people want to lead in it, instead of making them live as if they were executing a program written by the architect.

In software, it means you should give users a few basic elements that they can combine as they wish, like Lego. In math it means a proof that becomes the basis for a lot of new work is preferable to a proof that was difficult, but doesn't lead to future discoveries; in the sciences generally, citation is considered a rough indicator of merit.

10. Good Design Is Hard

If you look at the people who've done great work, one thing they all seem to have in common is that they worked very hard. Hard problems call for great efforts. When you have to climb a mountain you toss everything unnecessary out of your pack.

A story about Wang Shi (Note: A Chinese real estate tycoon and an avid adventurer who completed the Explorers Grand Slam. He submitted the Everest at age 53 and 60.) stuck with me.

A friend of his described Wang Shi’s approach, “When Wang Shi was climbing Mount Everest, whenever he reaches a new camp after every phase of climb, he goes straight into the tent, lies down and doesn’t move and doesn’t speak. His teammates thought he was dying. Wang Shi just wanted to conserve energy and spirit. The only thing on his mind was to reach the summit. Nothing else.”

The same friend described another climber, “After every phase of climb, he’d talk to the media, announcing his progress and impart his new-found wisdom. At about 8,000 meters of altitude. He’s too exhausted to continue and had to scale down regretfully.”

The moral of the story is that when you set a goal, you need to give it everything you’ve got; you have to be able to endure the loneliness to scale to new heights.

In design, when the problem is hard, it forces the designers to go with a simple, elegant design. Fashions and flourishes get knocked aside by the difficult business of solving the problem at all.

Not every kind of hard is good. There is good pain and bad pain. You want the kind of pain you get from going running, not the kind you get from stepping on a nail. A difficult problem could be good for a designer, but a fickle client or unreliable materials would not be.

When Bauhaus designers adopted Sullivan's "form follows function," what they meant was, form should follow function. And if function is hard enough, form is forced to follow it, because there is no effort to spare for error. Wild animals are beautiful because they have hard lives.

Time always softens the pain and makes things look like more fun than they really were. But who said everything has to be fun? Pain builds character. (Sometimes it builds products, too.)

11. Good Design Looks Easy

When we look at the work of great designers, we often think to ourselves, “That’s it? I could’ve done that.” Mostly this is an illusion.

A good, easy-to-use product may seem simplistic, but it’s the result of continuous improvements. The easy, conversational tone of good writing comes only on the eighth rewrite.

In science and engineering, some of the greatest discoveries seem like the simplest ideas. Listen to how Adam Savage tells the stories of how Eratosthenes calculated the Earth's circumference around 200 BC and how Hippolyte Fizeau measured the speed of light in 1849. Supposedly, anyone could have followed these simple, creative methods. But not many of us can make great scientific discoveries.

Some Leonardo heads are just a few lines. You look at them and you think, all you have to do is get eight or ten lines in the right place and you've made this beautiful portrait. Well, yes, but you have to get them in exactly the right place. The slightest error will make the whole thing collapse.

Line drawings are in fact the most difficult visual medium, because they demand near perfection. In math terms, they are a closed-form solution; lesser artists literally solve the same problems by successive approximation. One of the reasons kids give up drawing at ten or so is that they decide to start drawing like grownups, and one of the first things they try is a line drawing of a face. Smack!

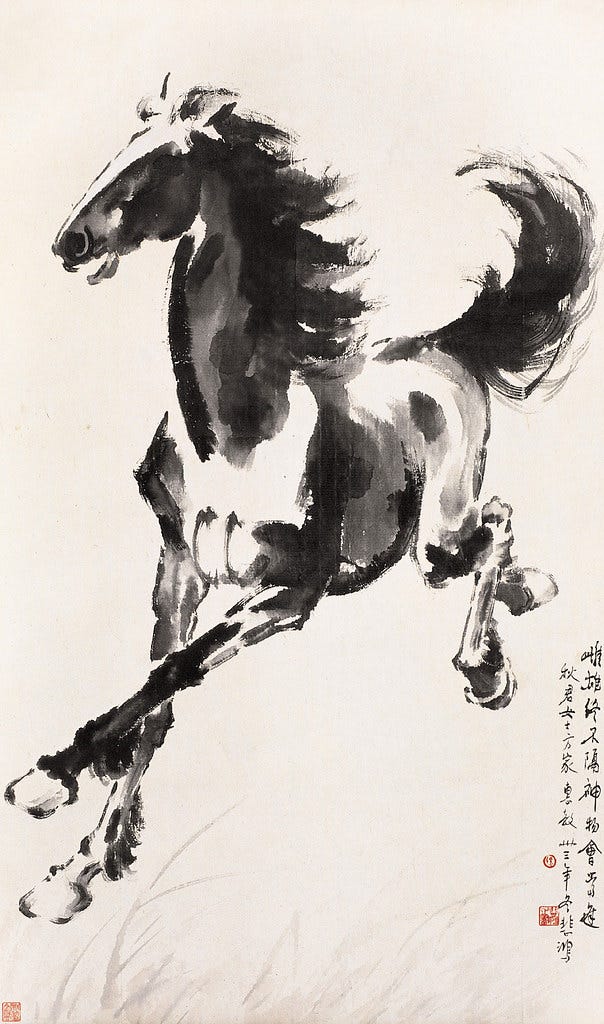

Traditional Chinese ink wash paintings are composed of nothing else but ink of different concentrations and brushstrokes of varying techniques. You can say traditional Chinese painters have the best ability in the world to capture the essence of a subject. Alas, in the modern age, we forget these abilities or no longer talk about them.

12. Good Design Is Often Strange

Some of the very best work has an uncanny quality: Euler's Formula, Bruegel's Hunters in the Snow, the SR-71, Lisp. They're not just beautiful, but strangely beautiful.

This strangeness is the style that we talk about. Every artist wants to develop a personal style. The work that you do try to develop a style often isn’t good. But if you just try to make good things, you'll inevitably do it in a distinctive way, just as each person walks in a distinctive way.

Michelangelo was not trying to paint like Michelangelo. He was just trying to paint well; he couldn't help painting like Michelangelo. Mies van der Rohe and Piet Mondrian didn’t set out to be Modernists. They just wanted to do their best work reflective of their times.

The only style worth having is the one you can't help. And this is especially true for strangeness. There is no shortcut to it. The only way to get there is to go through good and come out the other side.

13. Good Design Happens In Chunks

This is a strange one. Great works often come in chunks. The inhabitants of fifteenth century Florence included Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Donatello, Masaccio, Filippo Lippi, Fra Angelico, Verrocchio, Botticelli, Leonardo, and Michelangelo. Milan at the time was as big as Florence. How many fifteenth century Milanese artists can you name?

Something was happening in Florence in the fifteenth century. And it can't have been heredity, because it isn't happening now. You have to assume that whatever inborn ability Leonardo and Michelangelo had, there were people born in Milan with just as much. What happened to the Milanese Leonardo?

There are roughly a thousand times as many people alive in the US right now as lived in Florence during the fifteenth century. (Even more people in China.) A thousand Leonardos and a thousand Michelangelos walk among us. If DNA ruled, we should be greeted daily by artistic marvels. We aren't, and the reason is that to make Leonardo you need more than his innate ability. You also need Florence in 1450.

Nothing is more powerful than a community of talented people working on related problems. Genes count for little by comparison: being a genetic Leonardo was not enough to compensate for having been born near Milan instead of Florence. Today we move around more, but great work still comes disproportionately from a few hotspots: the Bauhaus, the Manhattan Project, the New Yorker, Lockheed's Skunk Works, Xerox Parc. (Silicon Valley)

At any given time there are a few hot topics and a few groups doing great work on them, and it's nearly impossible to do good work yourself if you're too far removed from one of these centers. You can push or pull these trends to some extent, but you can't break away from them.

14. Good Design Is Often Daring

At every period of history, people have believed things that were just ridiculous, and believed them so strongly that you risked ostracism or even violence by saying otherwise.

This problem afflicts not just every era, but in some degree every field. Much Renaissance art was in its time considered shockingly secular. Einstein's theory of relativity offended many contemporary physicists, and was not fully accepted for decades.

In George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, the government tightly controls information to keep the population in line, especially by banning books. Ring any bells? Censorship in China dates back to the Qin Dynasty, known as “the burning the books and burying-alive the [Confucian] scholars” in 213 BCE. Ovid was banished from Rome by the emperor Augustus for writing Ars Amatoria. Even in ancient Athens that celebrated intellect and free speech, reading certain books might still get you into trouble.

American activist Wendell Phillips said in a speech:

What gunpowder did for war, the printing press has done for the mind, and the statesman is no longer clad in the steel of special education, but every reading man is his judge.

Great ideas are often bold and stand against the ruling class. This helps to explain why most Chinese Nobel laureates either won their prizes overseas or in prison.

The ridiculousness of what we’ve discussed above may seem painfully obvious to us now. However, people then might not feel there’s anything wrong as they live through it.

In a post-screening audience Q&A for the movie In the Heat of the Sun (1994) at the Shanghai American School, a young girl asked the film’s director, Jiang Wen, “The teens in the movies were living through the Cultural Revolution, why were they so happy?”. Jiang Wen responded after a short pause, “I can see that you seem pretty happy right now at this stage of your life. When you grow older, you’ll realize what a terrible time we’re living in.”

In the same way, we seem to feel that everything around us is acceptable - C’est la vie. Only decades later, we realize that the previous era was awful.

What we need to worry about right now is not the Orwellian “Big Brother”, but our turning a blind eye to ugliness. If you want to discover great new things, you should pay particular attention to them.

It's easier to see ugliness than to imagine beauty. Most of the people who've made beautiful things seem to have done it by fixing something that they thought ugly. Great work usually seems to happen because someone sees something and thinks, I could do better than that.

Giotto saw traditional Byzantine madonnas painted according to a formula that had satisfied everyone for centuries, and to him they looked wooden and unnatural. Copernicus was so troubled by a hack that all his contemporaries could tolerate that he felt there must be a better solution. Steve Jobs thought all the “smartphones” in the market looked terrible, so he sought to create the phone he wanted.

Intolerance for ugliness is not in itself enough. You have to understand a field well before you develop a good nose for what needs fixing. You have to do your homework. But as you become expert in a field, you'll start to hear little voices saying, What a hack! There must be a better way. Don't ignore those voices. Cultivate them. The recipe for great work is: very exacting taste, plus the ability to gratify it.

Lessons

Good taste is not about discovering beauty; it’s about detecting ugliness.

Good design is not concerned with fashion; it focuses on making the best possible product.

Ornament is often a cover-up for the lack of substance. Good design needs to solve the real problem.

Good design is hard but looks easy.

Good design is daring, and constructive.

References

Original Article in Chinese

“The Taste Gap” by Ira Glass

Ten principles for good design by Dieter Rams

Taste For Makers (2002) by Paul Graham

Is There Such A Thing As Good Taste? (2021) by Paul Graham

Content-centric design by Prismatic

Find the article insightful? Please subscribe to receive more learnings from Chinese Internet companies and I’d appreciate it if you can leave a comment or help spread the word!

Such a beautiful written piece. It helps explain a lot why some of the most popular Chinese apps are cluttered yet brimming with users.