#031 - PM Lessons by Meituan Co-Founder - Pt 25: Demand and Supply Factors: Non-market Factors

6 mins read - raison d'être of non-market factors; public infrastructure; ecosystem perspective

👋 Hi! I’m Tao. As I learn about building products & startups, I collected some of the best content on these topics shared by successful Chinese entrepreneurs. I translate and share them in this newsletter. If you like more of this, please subscribe and help spread the word!

Factors Affecting Demand-Supply: Non-market Factors

Despite the attention and emphasis that we place on market factors, the non-market factors are also numerous and consequential, even in [a supposedly free-market economy like] the U.S.

For example, in September 2019, the state of California passed a law (Assembly Bill 5) that would require Uber and Lyft to classify their drivers as employees rather than as independent contractors and provide them with mandated employment benefits. (Note: Uber, Lyft, Doordash, Instacart, and Postmate then supported Proposition 22, passed in November 2020, which grants them an exemption from this law.) This is a classic non-market factor, from the legal side.

Non-market factors usually don’t matter in our operations, but when they do, they matter a great deal. Take ride-hailing for example. Ride-hailing is among the sectors in the Internet industry that are most affected by non-market factors. From the birth of Uber to the global popularity of ride-hailing, Uber has always had to deal with various authorities from governments of the world, [on top of industry competition, and so do Uber’s competitors]. Some regulators are more amenable to ride-hailing while others are less so. London revoked Uber’s license to operate in the city twice in the past and Uber ran into a lot of problems in Japan too.

(Note: Legality of ridesharing companies by jurisdiction)

The topic of interest here is how the non-market factors affect the operation of businesses and the demand and supply conditions. They are harder to understand than market factors because they work in much more complicated ways and it requires you to look at things from outside the industry. Non-market factors usually have their reasons to exist. To the free-market liberals, these non-market factors may seem completely unreasonable, but a lot of liberals are not fully open-minded.

Roads

Let’s start with a simple and mundane example - roads.

Roads are generally considered to be public goods. They are public infrastructure but they carry various market costs, like construction costs and maintenance costs. They also carry other indirect costs. If the roads are too wide, it may not be conducive for retail businesses in the city. People can’t see what’s on the other side of the street or are unwilling to walk over; a convenience store can only serve half the street or even less.

In additional, not only do you have a road in front of the block, but you also have roads at the sides of the block. For people who come from the side of the block, it’d be quite a distance to get to another block. Unfriendly traffic design to convenience stores is unfriendliness to consumers. Furthermore, in countries like Japan, convenience stores are a major employment source. They are also called mom-and-pop stores for a reason.

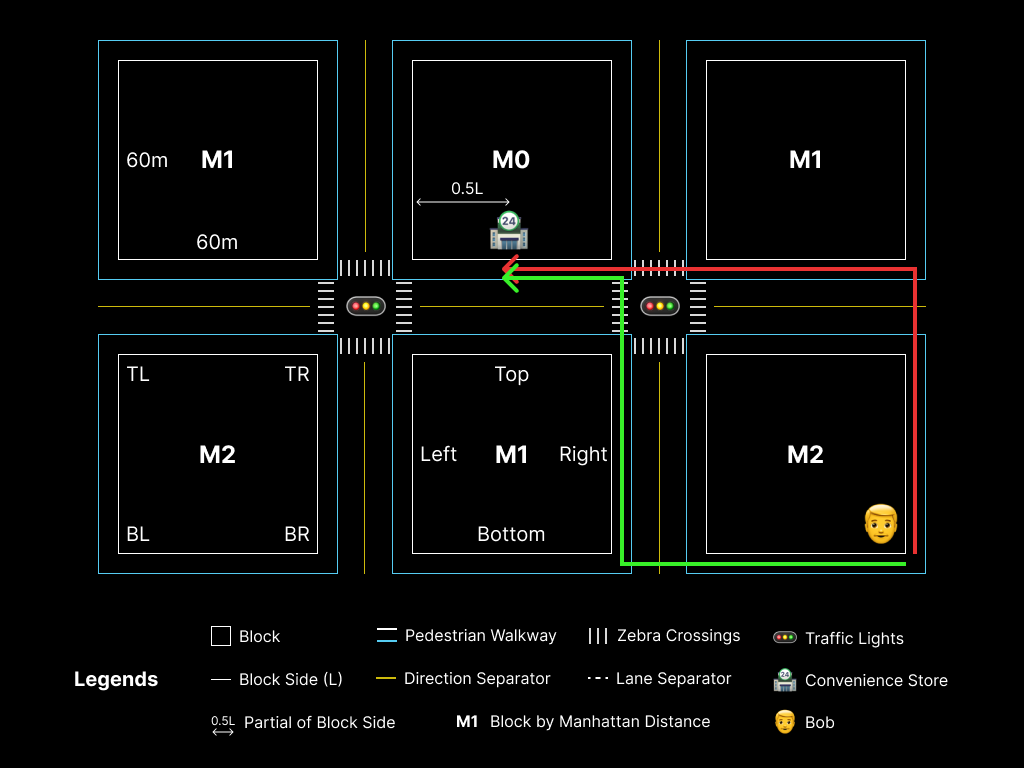

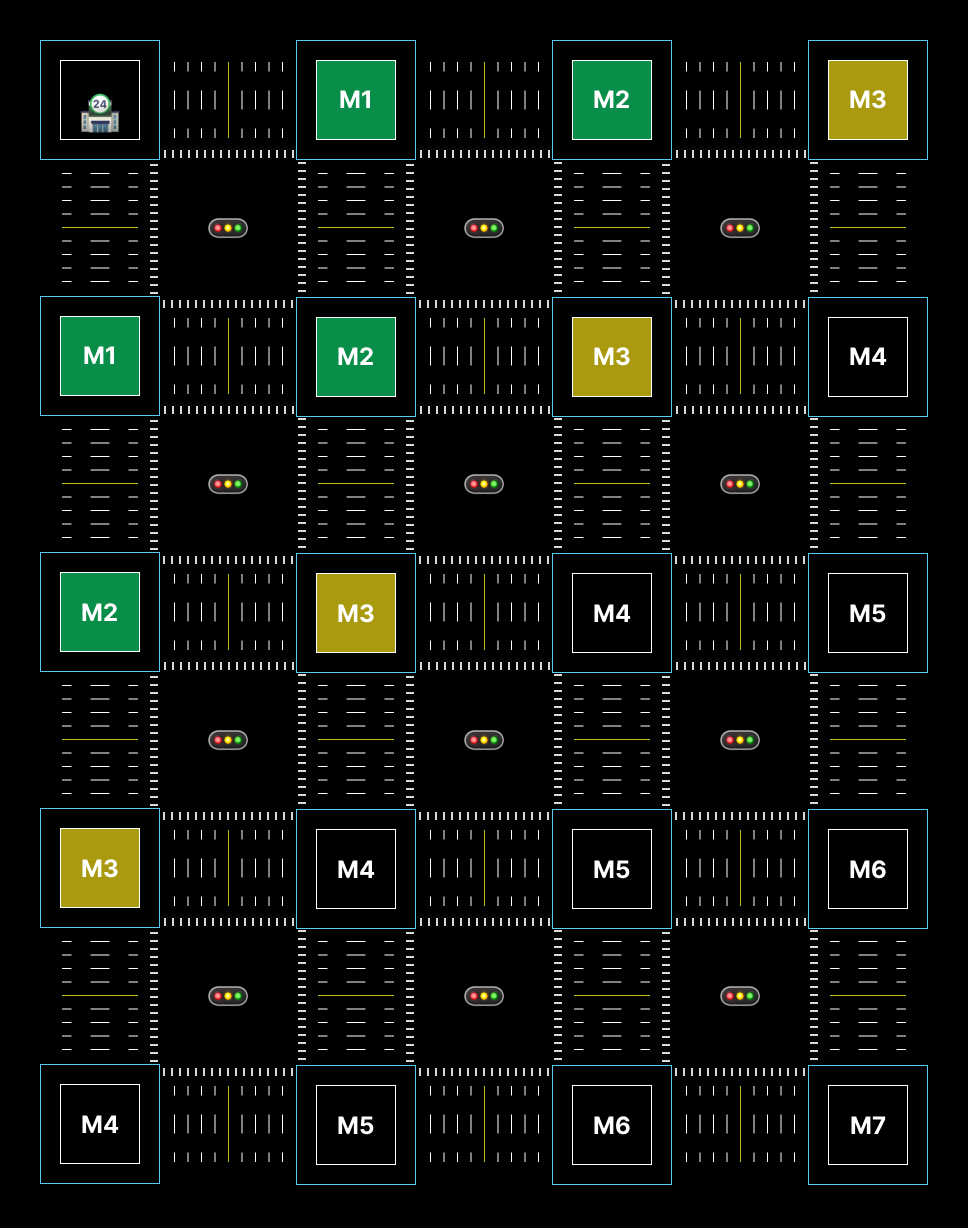

(Note: This part can be hard to understand without visualization. Hence I drew up the graphs below to help.)

(Note: To solve this, you need to apply the concept of Manhattan Distance with some modifications. Suppose our block is a square with sides of 60 meters, similar to the 200 ft x 200ft city blocks in Portland - What Is the Ideal Size for a City Block? And our road is a two-direction single lane road - each lane 3.5 meters, plus 3 meters each side for pedestrain walkways. Thus, the road in total is 13 meters wide.

Bob at the bottom-right corner of a M2 block wants to get to the store. Without diagonal crossing - hence applying Manhattan distance, he has to cross the road at least twice. The steps in Manhattan distance translate to how many times you have to cross the road. Depending on where you are at your block relative to the convenience store, you have to count the sides of the block into your walking distance as well. In Bob’s case, his total walking distance from the store is 60 + 13 + 60 +13 + 0.5 * 60 = 176m.)

(Note: With our previous foundation, we can now answer how the width of the roads impact retail businesses in cities. Suppose the walkable distance is 400 meters. Beyond that, people just don’t bother or they go to another shop. Our block size and road width are same as before - 60m and 13m. Within the walkable distance, all corners of M5 blocks can be effective serve by the convenience store while some corners of M6 blocks can be covered as well.)

(Note: Now with wider roads. A Class I city road in China is 80 meters - two-direction eight lanes plus verges and non-motor vehicle lanes as well as 15m-wide pedastrian walkways on each side. Our block size is still the same. Within the 400 meters walkable distance, now we can barely touch the M3 blocks.)

As such, there are limits as to how wide the roads should be. In that limited space, who gets to use it is the debate on the usage of public infrastructure. If you’ve been to the U.S., you may see a carpool lane in the middle of the highways. Only cars with multiple people in them can use this lane. If you use this lane, it means the road is better utilized - for the same period of time, same distance, and the same width of space, the road carried more people. Public infrastructure is used efficiently.

In another example, the bigger cities are all developing their public transportation. Subways are highly developed in Japan. (Note: Tokyo Has Built The World's Best Subway.) Subways are highly efficient in terms of the usage of roads. They don’t even take up surface space, and you can build multiple storeys underground.

In urban planning, you’d need to answer questions like how much time of the day a lane is reserved for buses, or how many carpool lanes you want to have on your highways.

Ride-hailing as compared to public transportation would be a much less efficient mode of transportation. Therefore, we cannot have too much of it. However, if you limit it too much, it’d be hard for people to get a ride.

Now we get to a philosophical question of should the need of getting a ride whenever you want be unlimitedly satisfied? Obviously, roads as a public good can’t support it.

An Ecosystem Perspective

You could also see these non-market factors as market factors as well. It’s just that the “market” is bigger than your industry. We need to look at it from the whole ecosystem perspective.

(Note: There’s an argument that some startups succeed by regulatory arbitrage - here and here. Uber is cheaper than taxis by avoiding licensing, labor protection, insurance, safety inspections, etc. and Airbnb is cheaper than hotels by skirting zoning laws.)

If we had priced ride-hailing higher, would that solve the problem? After all, before Uber, taxi rides were expensive.

Here comes another question. Using pricing to determine who gets to use the road, is that fair?

Maybe I’m not in the income bracket to use private transport every day, but I do today because I have to send my family member to the hospital quickly. Are you not gonna provide me with this transport option?

As such, we shouldn’t use a pure market approach to solve everything. The non-market factors may cause some markets to be artificially imbalanced in terms of demand and supply, but these imbalances may have a rationality to them.

In these kinds of markets, the tools that we have been using in managing demand and supply may not work anymore. You have to adjust your business model, product design, and operations to the context.

Find the article insightful? Please subscribe to receive more learnings from Chinese Internet companies and I’d appreciate it if you can leave a comment or help spread the word!