#030 - PM Lessons by Meituan Co-Founder - Pt 24: Demand and Supply Factors: Segmenting

8 mins read - High-end Disruption, The Hierarchy of Human Vanity

👋 Hi! I’m Tao. As I learn about building products & startups, I collected some of the best content on these topics shared by successful Chinese entrepreneurs. I translate and share them in this newsletter. If you like more of this, please subscribe and help spread the word!

Factors Affecting Demand-Supply: Segmenting

Segmenting is not easy. Different industries require different approaches and each segment within the industry would have its own demand-supply condition.

A common situation in segmenting is that the high-end segment has an abundance of supply while the low-end segment has a shortage.

Let me give you an example. In The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen was confident about his theory. However, a good explanation of the past isn’t enough to count as a good theory, it has to be able to predict the future. As such, Christensen predicted the rise of the electric vehicle (EV) industry, and that EVs will replace the fossil-fuel-burning cars that we have now. The path for EVs’ ascend will follow that of low-end disruption - starting with a niche market before eventually moving upmarket to take over the whole market.

The EV industry has all the right ingredients for a low-end disruption. EVs have fewer components than fuel cars, so theoretically it should cost half of what it takes to make a gasoline-power car to make an EV. And electricity is cheaper than fuel. In all, EVs should be a cheaper option, and it’s prime to enter a low-end niche market that incumbents don’t deem profitable, like school buses or mobility aids for the elderly (Note: where range and speed are not as much a concern).

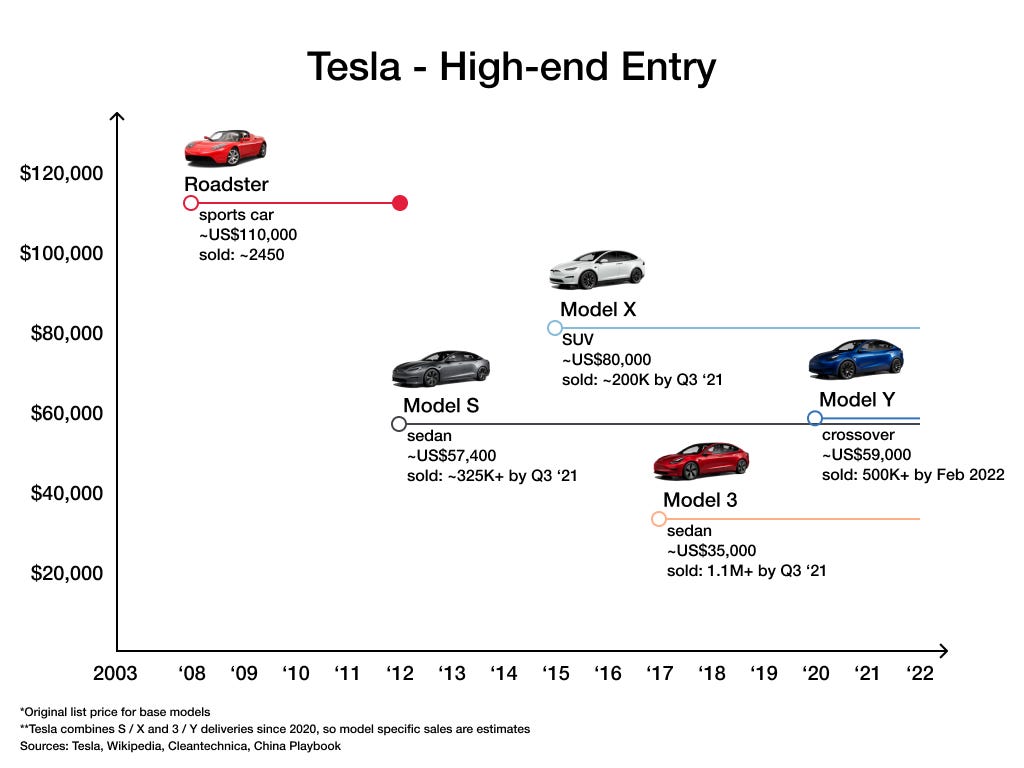

Unfortunately, the late Christensen got it wrong. Elon Musk started on the high end. First with sports cars (Roadster), then Model S, Model X, Model 3, and the upcoming Model Y. We shouldn’t discount Christensen’s theory just because of this. The disruption theory is one of the most important works on innovations. What he probably didn’t consider is segmenting.

(Note: For the record, Chistensen didn’t intend to predict the future of EV. He wrote the chapter as how he would approach the problem. And he did get some things right.)

I’ll also amend something I said earlier - that there are only two situations: demand outstrips supply or supply outstrips demand. That’s still true, but it may mislead you to focus on the surface. What’s worth paying more attention to is the underlying rule that brings about either situation.

Why did Telsa start with the high-end? One important attribute of the demand-supply condition with regard to high-end and low-end is [price] elasticity. Regardless of whether it’s an oversupply or undersupply, in the high-end market, both supply and demand have a greater elasticity (more responsive to price change). In contrast, on the low-end, both demand and supply are more inelastic (i.e. things tend to be necessities). The high-end customers have more disposable income, the relative cost of trial and error is low, and they can afford to buy a lot of products until they find something they like.

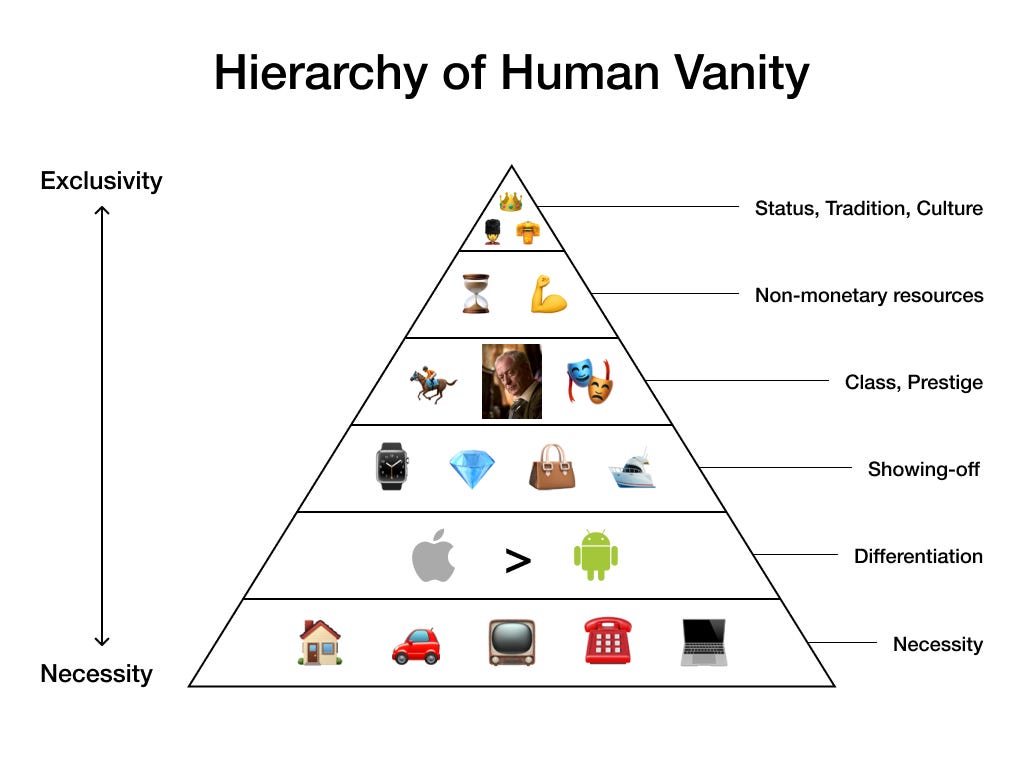

The Hierarchy of Human Vanity

Here’s the hierarchy of human vanity.

First, it’s the necessities. In the earlier years of consumerism, people compare whether your household has a TV, a fridge, an air conditioner, etc.

Then the degree of necessity declines, you will be okay without it but it’s still a case of haves vs. have-nots. iPhones are great, but Xiaomi works fine too. Phones have a particularly strong showing-off property since it’s in your hands all the time.

One level further, the item has even less practical value and is primarily used for showing-off, like expensive watches.

What comes after that? Well, we’re both rich, but you’re new money, I’m old money. I buy things your parents or grandparents wouldn’t dream of buying.

Further, if we’re both old money, money and prestige don’t matter anymore. I’m gonna compare time. I have a lot of idle time on my hands; I play golf all the time.

Further still, even if I have all the time in the world, I’m just not gonna do anything with it. I’m gonna keep my nails so long that I can’t even eat by myself. I’ll have servants to take care of my daily routine.

Give Them A Reason

For segmenting, people in different classes would have different things that they care about. Elon Musk was dead-on about the high-end customers - not only do they have the riches, but they also care about the environment. So Teslas were sold for their environmentally-friendly image. You’re so rich, try this scarce product that I have. It might not have enough mileage so it’s impractical for normal usage. But, first, you have to be rich to be willing to buy a car that you only occasionally drive, and second, you can show the world you think long-term, you care about the environment and the future of humanity.

From this entry point, let customers feel that they’re successful, and compassionate that they’ll buy a car that they won’t and can’t drive every day.

In the high-end market, the demand is so elastic that you just need to give them one reason they’ll be willing to try. In fact, all new technologies and new products have two paths of entry. One is from high-end, and the other from low-end. Most of the products that enter from the high-end are demand elastic. Even if the products are not “must-have”, and they’re not cheap, some people will be willing to buy if you give them a reason.

(Related: What Happened To Tesla’s First Car — The Roadster?)

Even if an industry would eventually go mainstream, rarely is the product suitable for the masses from the get-go. It has to make its way to the mainstream by premiumization if you’re coming from the low-end or commoditization if you’re coming from the high-end.

Tesla started with the most high-end market of sports cars. As its volume increased and technology matured, the costs came down and performance went up, which enabled Tesla to make products to serve a new segment that’s less high-end but greater in volume, and a positive feedback loop formed.

So, in short, the master plan is:

Build sports car

Use that money to build an affordable car

Use that money to build an even more affordable car

While doing above, also provide zero emission electric power generation options

Don’t tell anyone.

Different segments of the same demand would have drastic differences. As the demand goes from high-end to low-end, the necessity of the product increases. This is an important property of demand-supply from the segmenting perspective.

Epilogue

This issue I had a particularly hard time understanding. Wang Huiwen’s core message is simple enough - bringing price elasticity into demand-supply consideration. That’s Economics 101. However, he raised a counterpoint to what I’ve been thinking about startups all along - start small, start niche. And Elon Musk would probably have agreed with him. So I had to reconcile the differences. Below is my process. You can follow along if you want, and I’d be interested to hear what have you learned.

For me, I think “start small, start niche” is still true, but there are a lot of nuances to it. Ultimately, it’s about figuring out what people want.

Disruption Theory

The original disruption theory: Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave (1995) and the book The Innovator's Dilemma (1997)

A 2015 revision/clarification, considering Uber and Tesla not as disruptive: What Is Disruptive Innovation?

Two Theories of Disruption

New-Market Disruption: Established companies invest in technologies that their mainstream customers value (“sustaining technologies“) and ignore new technologies that don’t serve the needs of their mainstream customers. New entrants enter the market serving niche segments (nonconsumers) who find a use of the new technologies and the performance of new technologies improves at a rate faster than consumer demand (“disruptive technologies“) and they capture more market share as the technologies gradually satisfy mainstream use and eventually dominate.

Low-end Disruption: Incumbents provide ever-improving products to their most profitable and demanding customers. These products overserve the needs of less-demanding customers. New entrants enter the market by offering these low-end customers “good enough” products that are cheaper.

Discussion on “High-End Disruption”

Adherents to the HBS school of thought don’t seem to favor such a theory. The Persistent Myth Of High End Disruption

By seeing innovation as beyond just increasing performance, high-end disruption takes over the market by increasing affordability. High-End Disruption: Using Affordability to Measure Innovation

Flaws with Disruption Theory

Ben Thompson - 1. What Clayton Christensen Got Wrong 2. Apple and the Innovator’s Dilemma

The theory was developed at a time when most buyers are businesses. Unlike businesses, consumers are not perfectly rational. (Bounded rationality)

Not every product attribute is measurable.

“Good enough“ - some things, like user experience, can never be good enough.

I personally find it troublesome that a lot of the debates tend to focus on definitions and putting things nicely into two buckets - is it “disruptive”? If not, then everything else is “sustaining“. I don’t think that’s the whole picture.

Ben Thompson rightly points out another kind of technology - “Obsoletive”

High-end vs. Low-end for Internet Companies

One should note the difference between online businesses and offline businesses - the marginal costs of serving an additional customer (zero vs. non-zero, #18 - 4Ps in the Internet Age). The implications are:

It’s no longer that some companies serve the high-end segments and some serve the low-end segments. Instead, one company can serve everyone. Beyond Disruption. In that light, new theories/strategies need to be applied, like Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theory or Meituan’s Platform Strategy.

Innovations have to start small. The high-end segments with a greater willingness and ability to pay could be better as the initial customers. (As is the case for Under)

High-end vs. Low-end across Geographies + Technology Adoption Cycle

Naturally, one of the most important factors affecting disposable income is geography (i.e. developed vs. developing countries). With globalization and the ability of Internet companies to serve just everyone on the planet, it’s interesting to consider segmenting across markets.

Again, I’m citing Ben Thompson - The End of Trickle-Down Technology

A lot of people in developing countries are technology enthusiasts and visionaries who simply don’t have much money. They don’t want "trickle-down” technologies that are passed down from the high-end segments. They want the newest things. New business models and companies need to be built for them.

Conservatives in developed countries have been underestimated in their willingness to spend for products with better user experience.

Find the article insightful? Please subscribe to receive more learnings from Chinese Internet companies and I’d appreciate it if you can leave a comment or help spread the word!