#020 - Genki Forest Case Study - Part 2

12 mins read - Market Validation, Product is King, Don't Fuck with Users

👋 Hi! I’m Tao. As I learn about building products & startups, I collected some of the best content on these topics shared by successful Chinese entrepreneurs. I translate and share them in this newsletter. If you like more of this, please subscribe and help spread the word!

This is part 2 of the Genki Forest Case Study series. Part 1 is here.

If you want the original slide deck, share this newsletter on Twitter/Linkedin/Facebook or with your friends/colleagues via Slack, etc, and send a screenshot of the share to chinaplaybook@substack.com

03 Data-Driven Product Testing

Without market validation, even the best product idea is moot. The following product testing section is the most critical link in the chain.

As Focus Media's CEO, Jason Jiang, shared publically, in the early days, Genki Forest tested dozens of ideas before eventually deciding on the "Ran Tea" product. The soda product has even gone through more than one hundred different varieties. All that took slightly over a year.

How is Genki Forest able to conduct such rapid new product testing?

Let's look at one of the most frequently used methods by traditional consumer product companies - focus group discussion (FGD).

In FGD, 6-8 people are carefully selected from the target audience to form a focus group. A highly trained moderator will lead the session. The data is gathered through natural conversations with the interviewees and/or a questionnaire to find out how interviewees feel about the product or the brand.

The FGD is usually conducted in a conference room with video recording devices and a one-way mirror so that participants won't be aware that they're being monitored.

It's a practice that has been used in the FMCG industry for decades and naturally, it's proven to work. However, there are two problems with FGD:

It's expensive. Outsourcing to top marketing consultancies like Nielsen would cost tens of thousands of dollars.

It takes too long. From recruiting a suitable target audience to end results, the whole project could take 2-3 months.

As such, for traditional consumer companies to do all these, plus the bureaucratic approvals and whatnot, developing a new SKU could take up to a year.

As put by Genki Forest's former R&D Director, Ye Suping, the modus operandi of Genki Forest's R&D is fast trial and error.

Take taste as an example. Internally, Genki Forest conducts a taste test every day or two, then makes quick adjustments. The whole R&D cycle is controlled to be within 3-6 months. They can release a new product as soon as 3 months.

Again, Genki Forest uses the Internet playbook to conduct a "dimensionality reduction attack" in a traditional industry.

They straight borrowed how they used data and rapid testing when making games to experiment with new drinks. Data is the truth. The way is cheap and fast.

(Note: 降维打击 "Dimensionality Reduction Attack" is a popular term in the Chinese Internet parlance. Originated from the sci-fi "The Three-Body Problem". Literally, it means a high-dimension, say 4D, alien civilization can use a dimensionality reduction weapon on a lower-dimension, say 3D, civilization, to reduce its dimensionality to 2D, thereby catastrophically altered its environment so they can't exist anymore.

Metaphorically, it means using knowledge from a more advanced field to overpower your opponents or to change the competitive environment to your advantage.

It's a good book. Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg read it. I've not read it yet, but will get to it.)

If you work in tech, you've probably heard of "A/B test" or "multivariant test" - basically having N versions of different user interfaces or processes, in the same time duration, let similar groups of the target audience randomly visit/use the different versions to see which one performs the best. The best version is carried over in the next iteration. Rinse and repeat, and your product gets better.

The independent variable could be an ad banner and you invest a small amount of budget for each to see which one has a higher click-through rate; or a button in the app whether to be green or red.

In China or the West, it's already a very mature methodology. For example, Facebook probably has 10,000 tests running at any point in time, even if a test only improves 1% of a product metric.

Genki Forest adopts the same mentality to test packaging, selling point, concepts, etc. From what we've gathered, Genki Forest has hundreds of SKUs in the "inventory", constantly testing and comparing results. Once validated, the SKU is put to scaled production and promotion. In Tang's own words, "95% of our SKUs this year haven't even been released."

However, this data-driven testing methodology can't get you the results overnight. In fact, it's a slow discovery process. But you're constantly iterating and multiple products can break out concurrently.

Chronologically, these are roughly the phases:

Taste Test

E-commerce Test

Convenience Store Test

Ad Placement Test

DTC Channel Test

1. Taste Test

At the very beginning, there wasn't any method, the only requirement was speed.

For packaging design and recipe R&D, Genki Forest outsourced to the experts. For example, "Ran Tea" was created through partnering with an R&D center in Japan. After the new drink was developed, they'd first let the salespeople try it. If they feel it's okay, then it's rolled out.

Not long after, they found that this was not a reliable way at all. After all, salespeople are quite different from actual consumers.

Here came the first iteration - they instead gave the products to college students (born after 90-95) for the first round of internal testing.

2. E-commerce Test

Obviously, online tests can provide a much richer and accurate data set for evaluation.

Genki Forest would list the products that passed the first round of taste tests on e-commerce platforms, mainly Tmall and JD, to see if they can actually sell. If the backend data indicate a new product passes the standard for scalability, then Genki Forest would then distribute it via offline channels.

This is a method still being used by them today.

For example, we believe that you probably have never seen the following product in supermarkets. However, in the Tmall shop, it records a monthly sales volume of 20K cartons. Exactly because it's still in the testing phase and the data doesn't seem to pass the standard, it's never rolled out offline.

3. Convenience Store Test

As offline is the primary purchase scenario for drinks, the actual behavior of consumers at shops is the one that should be tested the most.

To overcome the difficulty of getting data offline, Genki Forest chose a very straightforward method - they'd place the new SKU near competitor products, and through human monitoring or camera recording, to see what consumers would do when selecting products.

Through data such as "head-turning rate" (Note: I think it’s self-explanatory.), they can get a clear representation of consumer reactions and whether this new SKU will be popular.

Of course, to let the product be as close to the target audience as possible, convenience stores are the best choice. In the earliest days, Genki Forest tested at Bianlifeng stores. (Note: Bianlifeng 便利蜂, a tech-driven convenience store chain.)

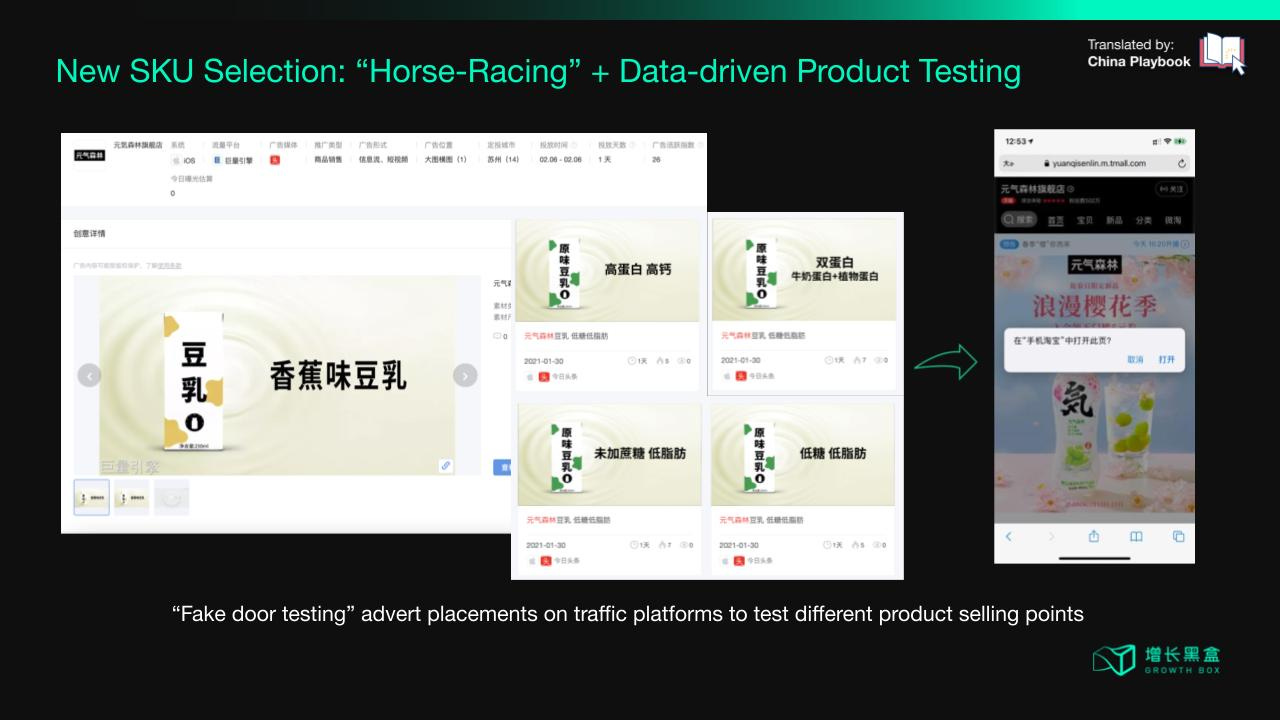

4. Ad Placement Test

We discovered that Genki Forest places information stream ads on Taotiao, to test product selling points.

For example, Genki Forest may release a soy milk product in the future, so they placed multiple different ad copies, each emphasizing different selling points, such as "high protein, high calcium", "double protein" (Note: animal and plant), "zero cane sugar, low fat", "low sugar, low fat". Click on the ad will lead you to their Tmall page, but no actual product is being sold. (Note: i.e. Fake door testing.)

With audience groups being controlled, the click-through rates on different selling points can tell which messaging resonates better with consumers. Testing this way provides rich data and is very cost-effective.

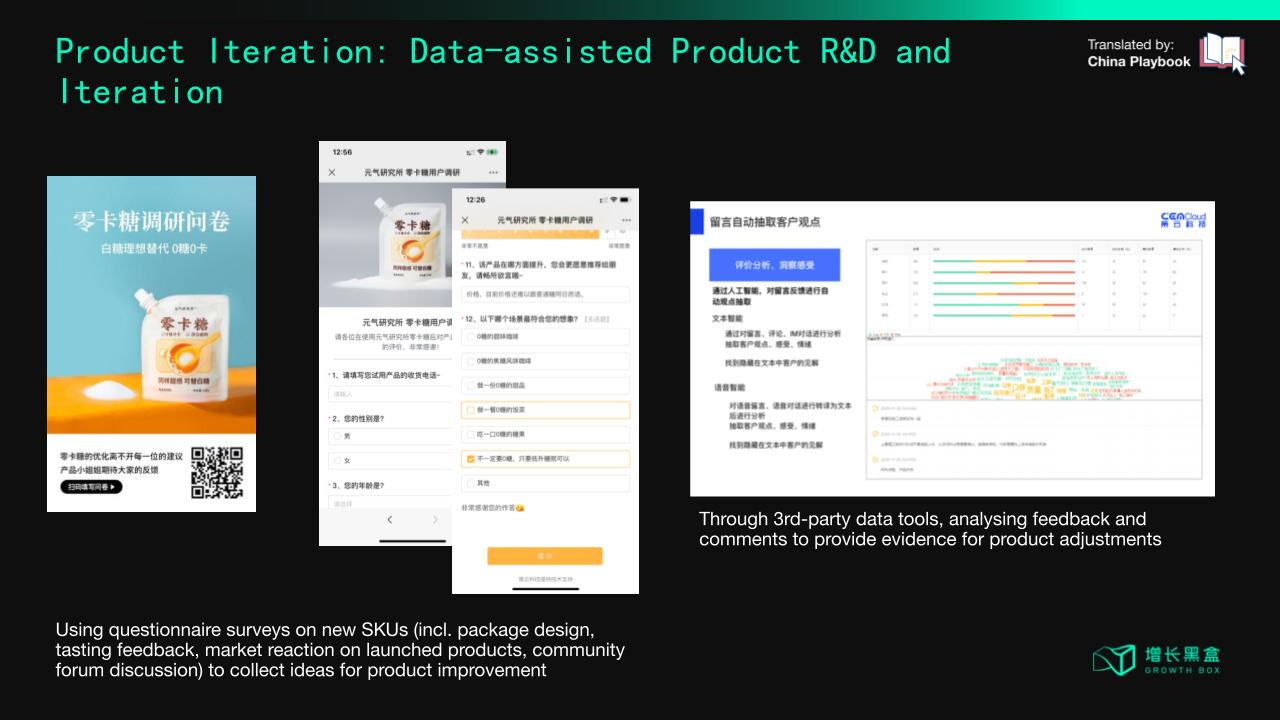

5. DTC Channel Test

Be it a questionnaire survey or a tasting, it's a commodity method used by everyone. And with these traditional methods, the inescapable problem is recruiting the right people to participate in the tests.

Therefore, in 2020, Genki Forest started getting into "private domain traffic" on WeChat.

The main purpose is of course to conduct tests in a cost-efficient way. They gave a name to the people in their private domain - "Experience Officers".

To illustrate, Genki Forest publishes new product testing campaigns through their mini-program on WeChat, "Genki Member Shop" (previously, "Genki Research Institute"). The people who are active on Genki Forest's mini-program are mostly loyal customers. They'd apply to be an "Experience Officer". Once chosen, they'd receive the free products shipped to them. (They just pay for shipping.)

After the experience officers received the products, they'd discuss them in the tasting chat groups and the product managers from Genki Forest would guide them to fill out questionnaires.

From our observation, the products that have been tested so far include:

"0 Cal Candy" - a candy that uses erythritol to replace white sugar.

Chick-breast Sausage - low fat

"Jewel Cup Yogurt" - a new product from Beihai Ranch 北海牧场, a subsidiary of Genki Forest

"Pop Pearl Bobo Yogurt"

"Alien" functional drink

Recently, Genki Forest has also been experimenting with big data tools to analyze feedbacks to unearth deeper insights.

You may ask: how come Genki Forest is able to inherit its Internet DNA, while the traditional incumbents can't learn from Internet companies?

We think the most important observation is the model is so new that it's hard to form a consensus on the methodology or experience.

Traditional companies have been the same methodologies for decades. No doubt, these methodologies have been time-tested and proven effective. If they were to use a completely different logic, it would be very hard to convince the stakeholders. Stable income is almost always the highest priority for them.

To draw an analogy: why do finance people have had such a hard time accepting bitcoin? The crypto market is so new that the hundreds of years of experience from the stock market hardly applies.

The second observation is about the flexibility of the organizational structure.

In the early days, Genki Forest's product department accounted for 10% of the company's total headcount. Even in 2020, they still have more than 50 people on the R&D team. (Note: Can't find the total headcount now.)

Every day, they're designing and experimenting with new product concepts, followed by testing. And they have high resource access rights.

In addition, their product development is organized in small groups, and they operate on the "horse-racing mechanism" prevalent in gaming companies, to inspire innovation through competition.

Conversely, in traditional companies, most of the R&D work is being outsourced. From product packaging to brand strategies, the marketing side is being outsourced to professional agencies. The product managers are usually few and they do mostly coordination work.

The upside of this model is that a few people are able to handle a very big operation, and the company sits on top of the value chain. The pursuit is maximum scale effect.

Obviously, if you fight your wars with hired mercenaries, you may improve your odds of winning some battles. But you would never have your own special forces. [that can save you in dire situations or is a sustainable competitive advantage]

04 Customer-centric Subsidization Model

A successful beverage product must overcome the inevitable challenge - taste!

Take Genki Forest's killer product - "Soda Sparkling Water" - it seemed to have solved a chronic problem of the industry.

Why?

Sugar-free healthy drinks are nothing new. Coca-Cola released its sugar-free version, Diet Coke, in 1982. Pepsi even led Coca-Cola by 18 years with the Diet Pepsi.

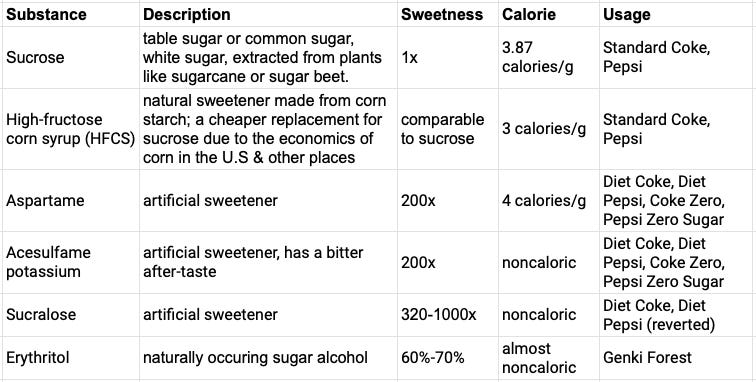

However, even today, almost all of the big brands' sugar-free carbonated drinks use artificial sweeteners like aspartame and acesulfame potassium in place of sugar.

The problem with artificial sweeteners is that it can be hard to meet consumers' tastes.

(Note: some history to illustrate the point on the importance of taste.)

Theoretically, the closer the taste of the sweetener is to the taste of sucrose, the more natural it feels and the better the "taste".

Aspartame is 200 times sweeter than sucrose, so it's hard to make a mix that tastes natural. And it contains calories.

Genki Forest solved the taste problem with erythritol - it's 60-70% as sweet as sucrose, so naturally, much easier to approximate natural sugar. More importantly, it's almost noncaloric.

From the patent of Genki Forest's soda, they first found that 7-8% sucrose concentration is the optimal taste, then used erythritol and sucralose to recreate the taste.

(Rough Translation:

The case listed is a soda drink, its ingredients include erythritol, sucralose, sodium bicarbonate, citric acid, food flavor, and water.

The case is intended to use ingredients to replace sucrose. Before deciding the substitute for sucrose, we conduct multiple tests to find out the optimal drink sweetness. The process is as such:

Using sodium bicarbonate, citric acid, food flavor, water, and sucrose as raw ingredients - sucrose as the source of sweetness - to testing for sweetness ranging from 3% to 11%, with an increment of 0.5%. Based on a tasting group of 50 people, with 3 tasting sessions for each test, the consolidated results report an optimal sweetness for this product at 7%-8% sucrose concentration. It’s lower than the similar products on the market with a 10%-11% sucrose concentration.

Thereafter, a variety of sugar substitutes are tested to approximate the 7%-8% sucrose concentration sweetness to find out if there are suitable low-calorie or noncaloric candidates. The process is as follows….)

(Note: Somehow I felt the need to figure out all the sugar substitutes from a product perspective, as summarized in the below chart. Obviously, it’s not an exhaustive research and doesn’t account for the taste, recipe implications, other health effects, etc.)

Here's the kicker. Erythritol was discovered in the 1850s, and it's commercially manufactured in China more than 15 years ago. Why don't the beverage giants use it?

Simple - the cost.

Based on the market data that we gathered, erythritol is 100 times more costly than aspartame.

This reveals to us the truth about the traditional beverage industry - the number one focus has always been profits and scale, not the customers.

Beverages are actually a highly lucrative business. The biggest moat is not the product itself, but the business model which brings high margins.

Coca-Cola has been consistently producing a gross margin of ~60%. The newly listed Nongfu Spring (SEHK: 9633) posts a margin of over 55%. The functional drinks brand, Eastroc Beverage, which recently submitted its IPO prospectus, also has a nearly 50% gross margin.

To scale this high-margin business as much as possible is what the big brands really care about.

Even if consumers may prefer the taste of the erythritol recipe, these companies are disincentivized to comply as it lowers their profit margins, no to mention the risk that the new taste may cater to too small a target audience.

Looking from their perspective, the chief concern for public companies is their earnings and the shareholders. No one would want their reporting numbers to look bad.

In a startup sharing organized by Sinovation Ventures, Tang repeatedly emphasized: in the current age, product is king, not distribution.

This is what he learned from paying much "tuition" in his web directories and gaming days. Pay attention to the second line on the slide.

Does this mean Genki Forest would practice what they preach and invest disproportionately more in product quality?

To verify whether Tang walks the talk, we gathered data from multiple sources to come up with an estimate for the manufacturing cost of Genki Forest's Soda Sparkling Water - it's about ¥2RMB.

Wholesalers (with underwriting) usually get a 15-bottles carton at the price of ¥38-42 RMB, so ¥2.5-2.8 RMB per bottle.

Essentially, the gross margin per bottle is ¥0.8 RMB (28%), much lower than what the traditional incumbents charge.

The extra cost is precisely spent on raw ingredients. From public data, the cost of raw ingredients of a 550ml Coke is around ¥0.2 RMB. In contrast, the cost for Genki Forest is at least ¥1 RMB.

In the early days, the cost of erythritol would even be higher for Genki Forest, as they import from the American company, Cargill.

If the marketing overhead is attributed to each bottle, the unit economics can barely break even. Plus operations, channel expansion, and other costs, we speculate that Genki Forest should be operating at a loss currently.

Nevertheless, Genki Forest is seizing the opportunity - put consumer demand as the top priority, subsidize the customers with cash-burning, and live by the idea that product is king.

Find the article insightful? Please subscribe to receive more learnings from Chinese Internet companies and I’d appreciate it if you can leave a comment or help spread the word!

If in a breverage industry margins are moat, so in a longer run how will Genki build a moat?